What is it that attracts creative people? Jobs, for sure. But what is needed before the jobs appear? A creative environment is a good place to start.

Austin began its transformation into one of America’s great cities in an inauspicious way. The Austin of today began with the music of yesterday.

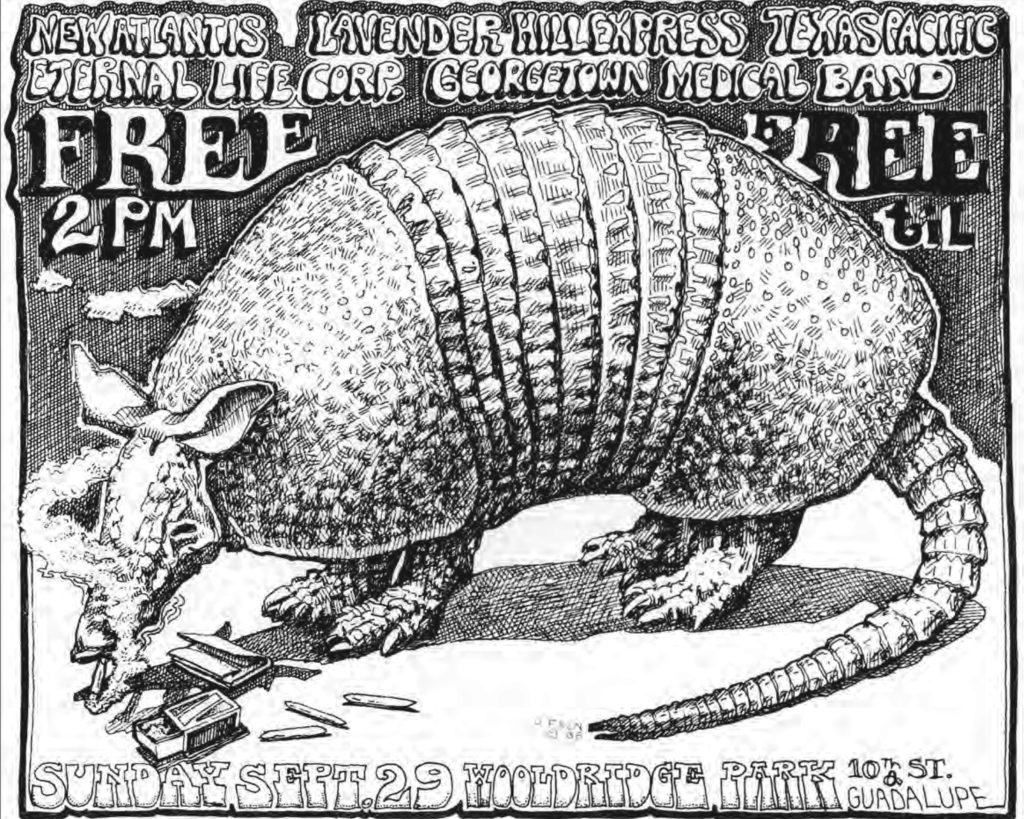

On September 29, 1968, local musicians held a benefit at Wooldridge Square. Jim Franklin, a local artist, designed a poster for that event. With the poster, Jim introduced what would become the new Austin’s symbol – the armadillo. With this event, the new Austin, the Austin of Keep Austin Weird, had a birthplace and a brand.

In 1970, Eddie Wilson, inspired by Franklin’s art, named his new music venue the Armadillo World Headquarters (AWH). On August 12, 1972, a newly arrived Willie Nelson first appeared at AWH, and he later invited his Nashville friends to join him. With the AWH, the new Austin found a home.

With this event, the new Austin, the Austin of Keep Austin Weird, had a birthplace and a brand.

Places that succeed in attracting and retaining creative class people prosper; those that fail don’t.”

— Richard Florida

In 1974, Austin City Limits began its lengthy run, and Eeyore’s Birthday moved to Pease Park from its quiet beginning on the University of Texas campus. Cliffton Antone opened Antone’s on East 6th in 1975, accelerating the transformation of Austin into the “Live Music Capital of the World.”

Civil rights progress marched through Austin, as well. On March 9, 1962, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to the University of Texas and spoke in front of 1,200 people at the Texas Union Ballroom. “Old Man Segregation is on his deathbed,” King said to the crowd. “The only question is how expensive the South is going to make the funeral.”

In August 1963, nearly 4,000 civil rights activists marched from the Capitol to Wooldridge Square, led by Booker T. Bonner. Austin’s Lyndon Baines Johnson, who announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate in 1948 from Wooldridge Square’s bandstand, as president signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The Economy Furniture factory strike in 1968 energized the Latino community. By the early 1970s, the creative forces of Austin’s Latino and African-American communities, previously balkanized by Jim Crow, swept into the mainstream.

Musicians, artists, and an eclectic collection of creatives began to relocate to our odd little community. In 1978, twenty-five-year-old college dropout John Mackey opened SaferWay, and two years later a merger led to the first Whole Foods Store. Whole Foods sold natural foods to our growing community of creatives.

Michael Dell began building and selling personal computers from his dorm room at the University of Texas in 1984 at the age of 19. Remember; in the early days computers were countercultural (Steve Jobs named his company after the Beatles’ label). South-by-Southwest started in 1987, and by 2000 we were concerned as to how we might Keep Austin Weird.

The more I study Austin, the more I am convinced that Austin is a textbook example of the creative community. Keep Austin Weird is just another way of saying Keep Austin Creative. Austin’s creative community, that which led us out of a white-rocks-and-cedar-trees, hardscrabble existence, can be traced to places such as Wooldridge Square and the improbable symbol of a pot-smoking armadillo.