William Barton settled near a springs west of the mouth of Shoal Creek in the 1830’s. He left a canoe on the north bank of the Colorado River so that people in the new settlement of Austin could visit his namesake. Barton’s canoe remained the only transportation across the river until the establishment of ferries in the late 1840s.

John J. Grumbles set up a regular ferry at Shoal Creek, at the western edge of the city, where William Barton kept his canoe. Shoal Creek remained one of the most important river crossings until the construction of permanent bridges.

Narrative is the way in which we understand our world and our place in it. Yet, the stories that comprise narrative are mutable and dynamic. We build our narratives with bricks that are still wet and easily shaped.

Over time and space, stories evolve. Eventually, an evolved story will become a new species, a social construct bearing little resemblance to the actual event or action it purportedly describes.

Narratives typically contain a rich and varied array of stories and ideas; however, at any given time, a certain set of stories (and memories) tends to dominate. In other words, there is a dominant narrative that society, in general, follows.

The interpreter’s responsibility is to offer a narrative that extends outside the bounds of that which is in vogue. In other words, the interpreter’s task is to challenge the public to consider interpretations that extend beyond those in current use. The interpreter’s job is to reveal what is hidden under the veneer of convention.

The interpreter’s job is to reveal what is hidden under the veneer of convention.

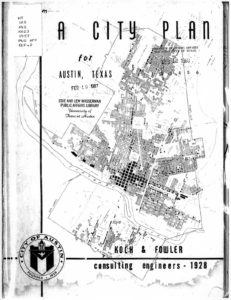

Stories convey something about what we believe to be stable in the world. Yet, contrast the image above to what we know of Billy Barton’s Austin in the 1830’s. In dynamic cities such as Austin, nothing could be less stable than the community. The median age of an Austin resident is 31. Half of Austin’s citizens were born outside of Texas; 20% were born outside of the United States.

Austin as a society is as unstable as its landscape. In this unstable and rapidly evolving environment, history unspoken or unrecognized is history quickly forgotten. The prevailing narrative becomes increasingly incomplete.

Here is one example. Austin is a city divided. Most of the minority community (African-American, Latino) lives east of Interstate 35. The reason is rooted in forgotten history. The 1928 Austin City Plan recommended the creation of a “negro district” east of East Avenue (now I-35). According to the engineers (Koch and Fowler) who developed this city plan;

In our studies in Austin we have found that the negroes are present in small numbers, in practically all sections of the city, excepting the area just east of East Avenue and south of the City Cemetery. This area seems to be all negro population. It is our recommendation that the nearest approach to the solution of the race segregation problem will be the recommendation of this district as a negro district, and that all the facilities and conveniences be provided the negroes in this district, as an incentive to draw the negro population to this area.

And, it worked. Most of Austin’s Latino and African-American population settled in East Austin, and has remained there ever since. With the city’s explosive growth, however, developers have discovered that East Austin is ripe for gentrification. East Austin is being redeveloped at breakneck speed, and many long-time residents are fighting a wave of gentrification that is crashing over their neighborhoods. Many see this as another instance of displacement at the hands of the descendants of those who displaced them in the 1920s.

What if no one is aware of the 1928 City Plan, or the decades of battles that were fought by Latino and African-American communities to gain their civil rights? What if no one has heard of Sweatt v Painter, or the battle over the Crosstown Expressway, or the conflict over renaming West 19th after Martin Luther King? All of this happened before most Austinites were born.

Unless this history is shared by the community, for the community, how will anyone know? The inevitable result of this gentrification is a community that feels under attack, developers that are increasingly impatient with the city, and a city government that is perplexed and ill-equipped to offer solutions.

The inevitable result of gentrification is a community that feels under attack, developers that are increasingly impatient with the city, and a city government that is perplexed and ill-equipped to offer solutions.

History that is unspoken is history that is forgotten. When history is untold, a fiction moves in to fill the void. And, this “new” history, as expressed through stories and memories, shapes actions. History informs the future, even when its incorrect or misshapen.

One solution to this problem is to have interpreted history, in all of its permutations, accessible to the people. The cloistering of history within a museum or university warehouse isn’t enough. History cannot be the exclusive domain of academicians and the local historical society.

Civic spaces such as historical squares are ideal places for introducing the public to the history that shapes the present and influences the future. Civic spaces are common grounds, places where the community can come together to better understand, appreciate, and celebrate a shared heritage. Travelers learn about the soul of the community when visiting these spaces.

Fermata is working with the Downtown Austin Alliance, in partnership with the Austin Parks and Recreation Department, to develop interpretive strategies for the three remaining public squares: Brush, Republic, and Wooldridge. These squares, part of Edwin Waller’s 1839 plan for Austin, are Austin’s original civic spaces.

We believe that history must be part of our everyday lives. History is as much about now as it is about then. Historical narrative is a way in which we understand our world and our place in it. Without that narrative, we are lost.