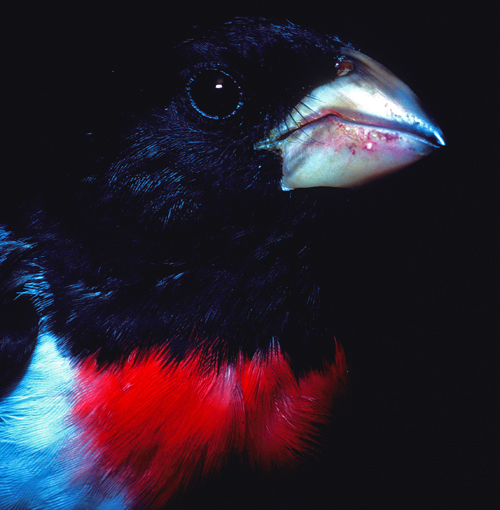

Purple juice spreads over my right shirt sleeve, gradually coalescing into a shape vaguely reminiscent of the Lesser Antilles. I peer upward, through the leaves, and see a rose-breasted grosbeak, its beak and breast equally tinted with a wine hue. The grosbeak gulps fruit with an audible appetite, each mulberry carefully manipulated in that outsized beak into its proper position before being inhaled into the bird’s gullet. Mistakes and choices are made, and a few of the berries slip from its grasp and fall to the ground or onto my shoulder.

Fingering my binoculars, other birds begin to appear within my focus. Buntings, orioles, tanagers, and grosbeaks are packed into this one tree, each enmeshed in a mulberry feeding frenzy. These are the mulberry birds, a cadre of audaciously decorated birds that are lured into my sight by the gravitational pull of one fruit – the mulberry.

In this instance, my mulberry tree is one of a row planted many years ago by Louis Smith in what became Houston Audubon’s Boy Scout Woods Bird Sanctuary in High Island, Texas. One fall Louis harvested a number of substantial branches from mulberries in the area, and then planted sections of the limbs along the pathway into the woods. The following spring these mulberries came to life, with their futures only briefly threatened when a couple of neighborhood kids decided to make their mark by uprooting the fledgling trees. I helped Louis replant the starts, and they seemed to take little notice of being yanked from the ground. I have often wondered how many individual birds have been nourished by Louis’s trees, and how many birders have been stained by their fruit.

The red mulberry (Morus rubra) is native to the eastern United States, spreading along the Texas coast as far south as the Coastal Bend. Birds (particularly migrants) sow the seeds widely through their droppings, and mulberries can be found sprouting in what would seem to be the most inhospitable locations. No matter, though. Come spring the fruit are guaranteed to attract a rich array of mulberry birds, no matter how bizarre the tree’s location might be.

The white mulberry (Morus alba) is a close cousin of the red, brought from Asia to America for silkworm culture in early colonial times. This species has naturalized and hybridized with the native red mulberry. In fact, the white mulberry is considered to be an invasive pest over much of its range. White mulberry is an aggressive pioneer, invading disturbed areas such as abandoned farm fields, highway right-of-ways, and undeveloped urban open spaces.

More ominously, the white mulberry threatens the viability of the red through genetic pollution (undesirable gene flow into wild populations). There are a number of white mulberry cultivars, including those that weep and those without fruit. To be honest, I have as much use for a fruitless mulberry as I do for a heatless jalapeño. The mulberry birds are oblivious to my reservations, and attack the fruits of both with equal zeal.

White mulberry leaves are the favored food for Bombyx mori (silkworm of the mulberry tree), the domesticated silkmoth whose cocoon is the source of silk. Chinese records indicate that the silk moth has been domesticated since 2700 B.C., and the species no longer exists in the wild. The domestic silk moth is now completely dependent on man for its survival and reproduction, and may be the most fundamentally domesticated animal in the world. How ironic that the fruit of the white mulberry is consumed by the wildest of creatures (migrant birds), while the leaves feed the most neutered.

The threat of genetic pollution is hardly limited to mulberries. The native wolf of the Gulf coast, the red wolf, has been on the receiving end of habitat loss and predator control since colonial times, and the remaining few freely interbreed with the expanding coyote. As a result fewer than 300 “pure” red wolves remain in existence.

Golden-winged and blue-winged warblers also interbreed, with the hybrids even given their own common names (the dominant Brewster’s, and the recessive Lawrence’s). The golden-winged favors early-succession habitats, such as abandoned farmlands. As disturbed lands reforest, the golden-winged is displaced. In addition, these anthropogenic (man-caused) habitats allow the blue-winged to expand into the golden-winged range. The blue-winged then freely hybridizes with the golden-winged, often replacing the golden-winged within fifty years of its initial arrival. There are concerns that the golden-winged warbler may well disappear as a viable species in the future.

Yet my concerns about man’s tinkering with nature are momentarily shelved as I relish the sight of this grosbeak working his way along the branches like a shopper breezing through the produce section. Each fruit is individually inspected and assessed according to criteria known only to grosbeaks. Is this fruit ripe? Is this fruit sweet? Is this fruit blemished? I also wonder if each individual grosbeak has a particularly taste in mulberries, or does the need for nourishment after a nonstop flight over the Gulf of Mexico trump taste. I can only imagine what drives this grosbeak to choose one mulberry (tree and fruit) over the others, but in the end choices are made. My grosbeak is particular.

My grosbeak is also a short timer, wasting little time with this meal before continuing away from High Island to the forests of the eastern U.S. and Canada. This mulberry tree, here by plan, annually attracts birds that ultimately span thousands of miles of breeding and wintering range. For one moment, one brief instance, this tree is festooned with birds brought together by fruit rather than geography. And, for this same moment, I am brought together with the mulberry birds, also by plan.

Ted Eubanks

17 October 2010