Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler—Albert Einstein

The third principle of the Culture of Conservation is to keep the message simple. Effective marketing is little more than simple messages and images repeated endlessly. Remember the earlier quote that 93% of American children can recognize McDonalds by the golden arches? I wonder what the percentage is now for the Japanese?

Simple messages and images rise above the cacophony that is modern life. Simplicity and volume (both amplitude and amount) help messages battle through the noise. Doubt this? According to the Associated Press, BP’s been spending more than $5 million a week on advertising since the blowout. Remember BPs original simple message? Beyond Petroleum.

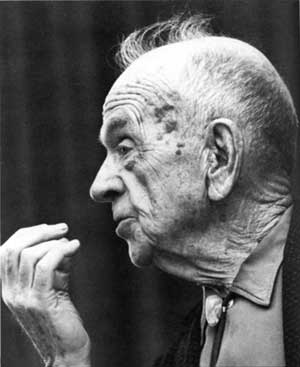

Freeman Tilden inspired what we now know as the interpretation profession. Tilden stressed the need for interpreters (guides, museum staff, National Park Service employees and the like) to know their audiences. My impression is that most conservation groups consider their members to be the audience. No wonder the messages are so obtuse, and geared toward fund raising.

Why? Because I believe that conservation as a movement is fundamentally inept when it comes to devising ways in which people can relate to our work (another of Tilden’s principals).

Rather than continue to offer Tilden’s principles in a piecemeal fashion, here are the six principles from Interpreting Our Heritage:

1. Any interpretation that does not somehow relate what is being displayed or described to something within the personality or experience of the visitor will be sterile.

2. Information, as such, is not interpretation. Interpretation is revelation based upon information. But they are entirely different things. However, all interpretation include information.

3. Interpretation is an art, which combines many arts, whether the materials presented are scientific, historical, or architectural. Any art is to some degree teachable.

4. The chief aim of interpretation is not instruction but provocation.

5. Interpretation should aid to present a whole rather than a part and must address itself to the whole man rather than any phase.

6. Interpretation addressed to children should not be a dilution of the presentation to adults but should follow a fundamentally different approach. To be at its best it will require a separate program.

NAI offers a number of certification programs, and I endorse them all. Interestingly, most conservation groups do not have certified interpretive staff, a mistake in my opinion. But I also believe that there is a need for us in the profession to develop a certification program in conservation interpretation, a program that does not exist currently. For those interested in where we have taken this idea, there is information here on the Fermata blog.

The key to successful simplification, however, is (as Einstein said) to keep things simple but not too simple. In conservation we deal with complex issues like global warming, oil spills, biodiversity, and extinction. These topics do not lend themselves to simplicity. Yet, as Tilden stated, our presentations, programs, and messages must address the desires, experiences, and limitations of our audiences. In this way I agree with Tilden that interpretation is an art, one practiced well by a few. Read Enos Mills, Aldo Leopold, Edward Abbey, and Peter Matthiessen to get a sense of the interpretive art as it relates to conservation.

The National Park Service (NPS) has devised an equation to show the key components that go into the interpretive experience – (Kr + Ka) X AT = IO. Remember, however, that this is metaphor, not math. The equation states that a knowledge of the resource (Kr) plus a knowledge of the audience (Ka), multiplied by well-grounded interpretive techniques (AT), will create an interpretive opportunity (IO). The equation is often displayed as a teeter-totter, where an overemphasis on one factor, such as knowledge of the resource, can outweigh and overwhelm the audience and any interpretive technique. In my experience this is the chief failing of conservation groups. Yes, they can all impress with a knowledge of the resources, but most have no concept of how to communicate that knowledge or a conservation imperative to the audience.

Let’s recap. I have now presented three of the Culture of Conservation principles:

1. Take it to the street

2. Make space for place

3. Keep it simple, not simplistic

Keep tuned for the next principle – Aim straight for the heart.

Ted Eubanks

15 Sep 2010