The Fermata appraisal of recreation and entertainment opportunities in East Park, West Park, and the Wissahickon is final. For the past 18 months we have been exploring this most historic park system, and our recommendations are now complete. The Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department (PP&R) has been an honor and joy to work with, particularly Commissioner Mike DiBerardinis and his assistant Kathleen Muller. The entire staff has been unwaveringly supportive, and we thank all of them for their invaluable assistance. We have posted a PDF of this report in the Fermata library.

Tag Archives: Fairmount Park

The Culture of Conservation – Space for Place

A place for everything, everything in its place.

Benjamin Franklin

Everything in its place. In Franklin’s case, the place is Philadelphia. For the past year I have been helping Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, the nation’s first. More than 300 years ago, William Penn designed Philadelphia to be a “Greene Country Towne,” where squares, parks, and open spaces would allow residents to escape the pace and unhealthy conditions found in 17th-century European cities. In 1690 Governor Penn required for every five acres cleared one acre of forest should be preserved. Franklin led a commission to regulate waste water in the city (leading to the first waste water treatment in the country). Where I am working, Fairmount Park encompasses 9,200 acres, a full 10 percent of the land in Philadelphia (city and county).

Recently I have been rereading Jane Jacobs, and mulling over how our concepts about cities might also apply to conserved lands. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities she commented on how many of the City Beautiful centers failed, attracting not successful small business and shops but “tattoo parlors and second-hand-clothing stores, or else just nondescript, dispirited decay.” Jane died too soon. Perhaps it took cities like Philadelphia and Pittsburgh longer than she expected to revise their approaches to their once-celebrated centers. Philadelphia’s city center now ranks among the tops in the nation in downtown residents. Pittsburgh has been ranked by Forbes as America’s most livable city.

My work is with parks and open spaces, not with buildings and the urban core. Yet in recent years I have been increasingly interested in how these once flourishing cities, places where city leaders once invested in parks, museums, and grand esplanades, are now using these same inherited assets to reinvent themselves. These cultural, historical, and natural amenities anchor cities, and offer a stable platform for reconstructing and reinvigorating the society that surrounds them. Yet there is an undeniable rule of law that governs these places. To have treasured places, you must protect treasured spaces.

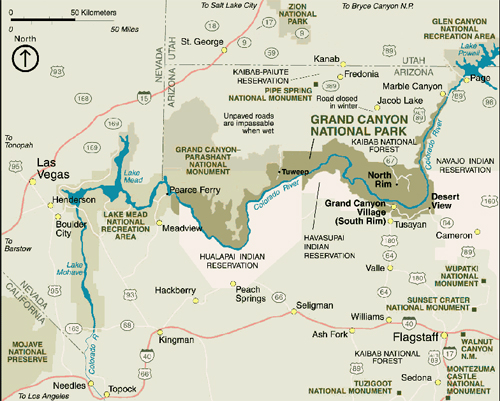

How do the two differ? Place, for my purposes, is a physical location with defined metes and bounds. For example, the national park lands that include the Grand Canyon can be shown on a map with clear, defined boundaries. Most conservation organizations and land conservancies are focused on place.

Space, however, is psychological rather than physical. The federal lands that comprise Grand Canyon National Park do not limit the psychological space occupied by the Grand Canyon. That space includes Flagstaff, Sedona, the Havasupai Indian Reservation, the bordering national forest land, the smell of pinyon burning, the sounds of elk bugling, the crashing of the Colorado River as it slices through the canyon, and the colors of a sunset painted on the canyon walls. The Grand Canyon space is filled individually, with each person defining “Grand Canyon” based on their personal experiences and exposure. Space is the sum of all that is known and felt about a given place or group of places. Space is identity rather than body. While place has discrete, physical boundaries, space has soft, amorphous edges. Space is of the mind; place is of the land.

This chart shows a rudimentary space model for the Grand Canyon. The number of places I am showing is arbitrary; certainly, Grand Canyon is a far more complex landscape than this. More importantly, this model should be three dimensional (at least more than this Powerpoint chart illustrates). If you have visited the Grand Canyon, what do you recall about your visit? What spaces do these sensations occupy in your mind? Mine would include the smell of pinyon in a Flagstaff restaurant, an American three-toed woodpecker feeding in a burned area in the national forest, and the thrill of standing with my grandchildren at the South Rim mesmerized by the sunset.

Here are a couple of additional examples to mull over. The White House is a small place, occupying an extraordinarily large space in the American mind. The Alamo in San Antonio is similar. Many visitors to the Alamo are surprised that the mission is so small. Fairmount Park is an expansive, diverse place, but a small space. Few people know the actual extent of the Fairmount Park system, and relate only to their favorite place within it.

Conservation agencies and organizations are understandably focused on place. A place can be purchased, fenced, posted, and protected. However, how people relate to these efforts (and their willingness to support their protection) is defined by their personal perception of the space. Whether or not they value a place is determined by how they perceive the space.

Therefore my second step in reshaping our conservation movement (remember the first? Take it to the streets!) is that we need to create more spaces for places. The world is full of place conservers. We need more space makers.

McDonalds is a fast-food joint that sells hamburgers. There are around 14,000 McDonalds in the US, and each occupies a discrete place or location. But what about the space that McDonalds occupies in the American psyche? Consider that 93% of American children can identify a McDonalds by its golden arches. How many can identify a national park by the arrowhead logo? Which has a larger American space – McDonalds or the National Park Service?

Fortunately, the technology exists for us to create space for place. We do not need McDonalds advertising budget to construct an American space for American places. Consider all of the places that should be brought to the attention of the public, and the spaces they combine to form. I am interested in the smallest neighborhood park to Yellowstone National Park. How many are in your community? What spaces do they occupy in your and your neighbor’s lives?

The U.S. is in the midst of the worst economic recession in my lifetime. When state and federal budgets are slashed, who gets cut first? Places, such as parks, refuges, and sanctuaries are the first to go. Is this because they are not valuable places? Of course not. Political leaders hatchet our treasured places because they occupy limited space in the interests and concerns of the voting public. In other words, our places are easy marks, and we who strive to protect them are defenseless chumps.

I am not willing to go through another budget or political cycle so defenseless. We must develop the tools to collect our places into aggregations that occupy critical social space in the lives of our citizens. It is not enough to limit our efforts to simply protecting places. We have no choice but to squeeze ourselves into the American space.

I do have ideas about how to accomplish this, and I will write more in the near future. We need the tools to stitch these places into seamless spaces, and the media necessary to present these spaces to America.

In the meantime, let me remind you of my first two steps of a renewed conservation movement:

1. Take it to the street

2. Space for place

Ted Eubanks

13 Sep 2010

Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park

Political currents steer us all, and at their whim. Since the advent of the Rendell Administration in Pennsylvania Fermata has been working alongside the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources in a series of progressive conservation efforts. The initiatives (called CLIs, or Conservation Landscape Initiatives) have matured to a point where they are beginning to influence other states as well the federal government. The CLIs were the brainchild of Michael DiBerardinis, who served as the Secretary of the agency. Secretary DiBernardinis is now Commissioner DiBerardinis of the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department. As a native Philadelphian, the Commissioner felt it time to return home from Harrisburg. With a new administration certain (Governor Rendell is at the end of his 2nd term), Commissioner DiBerardinis decided to tackle one more challenge – the reshaping of Fairmount Park, the Philadelphia park system.

Fortunately the Commissioner has asked Fermata to help (i.e., lucky for us). The Commissioner is one of the most progressive and inspiring conservation and recreation leaders in the country, and we are honored to work for him again. Fermata’s Ted Eubanks has now visited Philadelphia on four occasions, and has come away in awe of the history of Fairmount Park. Even though many Philadelphians tire of hearing about their firsts (America’s first hospital, zoo, art museum, free library), we believe it important to remind our public that Fairmount is America’s first park. Over the centuries the park has grown to include the cultural and scientific centers arrayed along Ben Franklin Parkway, the Wissahickon Valley, the Schuylkill trail, East and West Park, and a mind-bending assortment of facilities, lands, staff, and volunteers. Fairmount is America’s largest urban park, and the system offers more park land per capita than any American city over 1 million population.

Consider this. Standing in Love Park, you can walk up Ben Franklin Parkway to the Philadelphia Art Museum and the Water Works, connect to the Schuylkill River Trail and hike or bike to where connects with the Wissahickon Trail, continue up the Wissahickon to Forbidden Drive, follow Forbidden Drive to Northwestern Avenue, and for that entire 16 miles never leave park land. Hiking along Forbidden Road in the Wissahickon Valley you would never know that you are within in a stone’s throw of downtown Philadelphia. Fairmount is America’s great urban park, conserved and nurtured by the people of America’s first great city. For more information, go to Fairmount Park under Current Projects.

On the Road (again)

The next few weeks are dominated by travel. There is nothing like spring to entice one outside. This week I am in Scott County, assessing sites for a heritage tourism analysis. We are working with Carolyn Brackett, a Senior Program Associate with the Heritage Tourism Program, National Trust for Historic Preservation. After returning to Texas on Thursday I will be in Galveston, trying to finish dismantling the Houston office.

On Sunday I fly to Pittsburgh, and then spend next week in Pennsylvania. I am speaking at Pennsylvania Environmental Council’s Marcellus Shale conference Monday. I then travel to Harrisburg on Tuesday to attend the Pennsylvania Parks and Forests Foundation’s annual awards dinner that night. PA DCNR parks recently won the gold medal for being the best state park system in the nation, and that night we will all celebrate their success.

I will continue on to Philadelphia the following morning, and I will work the remainder of the week in Fairmount Park. The last time I visited Philadelphia we were hampered by the remainder of a blizzard, and it will be wonderful to see the park facilities exposed.

Finally I will fly to Chicago on Sundayt, and then drive to Valparaiso (Indiana) for a couple of days work on Indiana Beyond the Beach. We are about to unveil a number of new products regarding the BTB Discovery Trail, so stay tuned. I will blog from the road as I travel these next weeks.

Ted Eubanks

26 April 2010