What stands between our heritage and the inability of man to control his greed is law.

Europeans came to this country over 400 years ago, and were blessed by what they believed to be limitless resources. The land seemed fertile beyond reason or imagination, and wildlife could be harvested without concern for its diminishment. Or, so they thought.

Theodore Roosevelt is the better known of a generation that came to realize the risk rapaciousness and predatory greed presented to our country’s natural heritage. Roosevelt and his colleagues such as Gifford Pinchot, Edgar Lee Hewett, John Muir, Frank Chapman, John F. Lacey, J.T. Rothrock, Myra Lloyd Dock, and George Bird Grinnell could see that without direct action, without government involvement, the feast would continue unchecked, leaving only a few moldy scraps for future generations.

Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot were faced with millions of acres of cutover lands being abandoned after they were timbered. Fires constantly raged through the debris left after the harvesting; watersheds were eroding, silting rivers and streams.

States (such as New York and Pennsylvania) and the federal government moved in to begin the restoration of these lands. They bought these worthless lands from owners eager to sell.

Roosevelt recognized that we also needed a system of refuges where wildlife could flourish. One reason? We needed sources of wildlife, especially game animals. for restoring those lost in the Big Cut. Pennsylvania, for example, began reintroducing Rocky Mountain elk (the native eastern elk Cervus canadensis canadensis was extinct by this time) and white-tailed deer (!) in the early 1900s.

Edgar Lee Hewett’s inspiration, the Antiquities Act, and John F. Lacey’s Lacey Act (Lacey also helped with the Antiquities Act) are examples of legislation that pushed the federal government into conservation. The modern game laws were enacted in the early 1900s, bringing market hunting under control. The National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service were created in this same period.

What stands between our heritage and the inability of man to control his greed is law. Through law, we established a system of public lands that is the envy of the world. Through law, we defined the limits to which we would allow our water and air to be fouled. And, through law, we protected land rights, establishing a clear demarcation between a public interest and one that is private.

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, currently occupied by a self-styled militia, is a perfect case in point. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “In 1908, wildlife photographers William L. Finley and Herman T. Bohlman discovered that most of the white herons (egrets) on Malheur Lake had been killed in 1898 by plume hunters. After 10 years, the white heron population still had not recovered. With backing from the Oregon Audubon Society, Finley and Bohlman proposed establishment of a bird reservation to protect birds, using Malheur, Mud, and Harney lakes.”

In other words, the Roosevelt administration set aside this property to help restore heron and egret populations devastated by the plume trade. Roosevelt’s original executive order included only those excess federal lands that had not been claimed by homesteaders under the federal programs that had been created to attract them. Eventually, additional lands were added to Malheur through purchase from willing sellers.

These are called public lands for a reason. We the people own them; we the people conserved them; we the people restored them.

Conservation and restoration efforts like Malheur have been funded by American taxpayers for well over a century. These are called public lands for a reason. We the people own them; we the people conserved them; we the people restored them.

The people who work for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the other state and federal land resource agencies have done a wonderful job working for us to protect our shared natural patrimony. The next time you get a chance, thank them for their service.

As for the people occupying Malheur, they are thieves trying to steal our shared natural heritage. There is nothing patriotic or admirable about thievery.

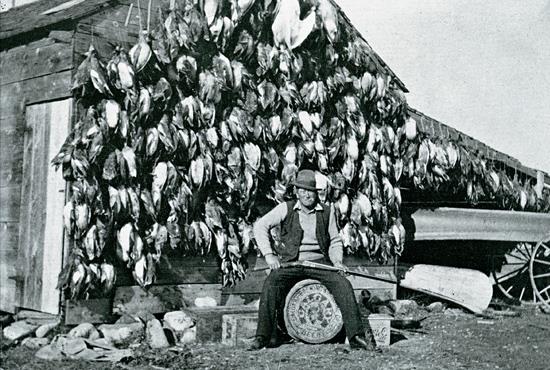

The people at Malheur would like to remove from the public domain assets that would accrue to themselves. They would like to return to a time when government had no role in protecting our national heritage. Look at the photographs that I have included in this article. They reflect that time.

Regardless of the strategy being used by the federal government to bring this stalemate at Malheur to a close, those occupying the refuge are breaking the law. Americans have worked for generations to conserve and restore this heritage once at risk, and now a handful of mindless ultra-rightests would like to snatch that heritage away.

I understand our government’s wish to not make these people martyrs. Waco is still too fresh in our memories. But, there is a limit to patience. These lands are owned by we the people. And we, the people, have a right to reclaim that which is ours.

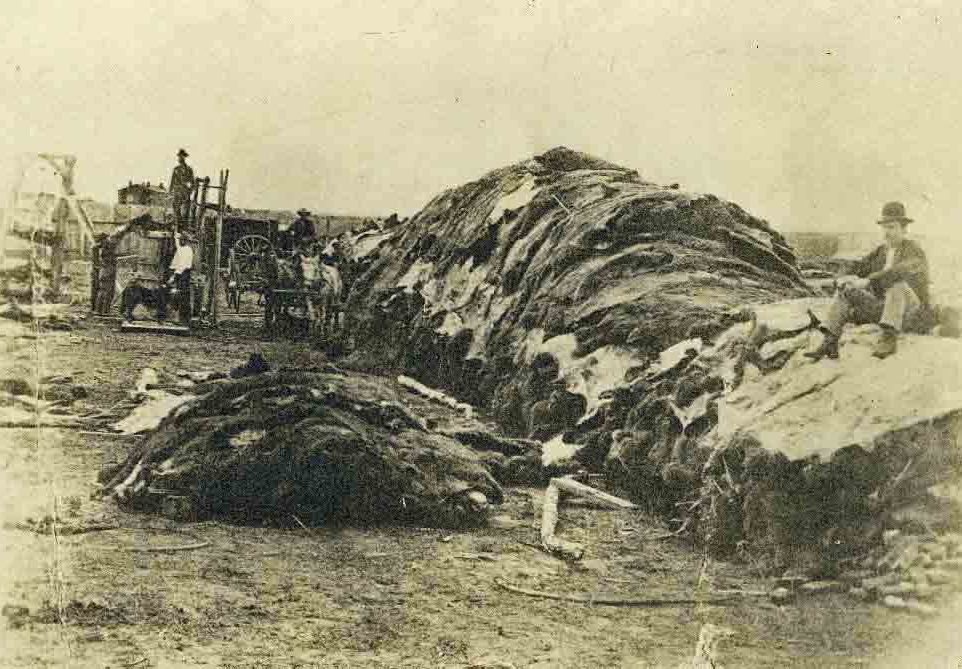

Here is one final photograph and anecdote to consider, this one from Western Colorado. These are bison hides.

The hides were often shipped by train to Pennsylvania and New York to be processed in tanneries. Some of these tanneries were in an area where I have worked, now call the Pennsylvania Wilds. I have walked around the ruins of these tanneries, a sobering stroll.

Most of the hemlocks in those forests, once called Penns Woods, were felled for their bark. Tanneries would first soak the hides in water, then lime, then tannic acid derived from the hemlock bark. Tanneries then dumped all of the waste (flesh, hair, lime, tannic acid) back into the streams and creeks where the tanneries preferred to be located. These tanneries proliferated in New York and Pennsylvania, any area with an abundance of water and hemlock.

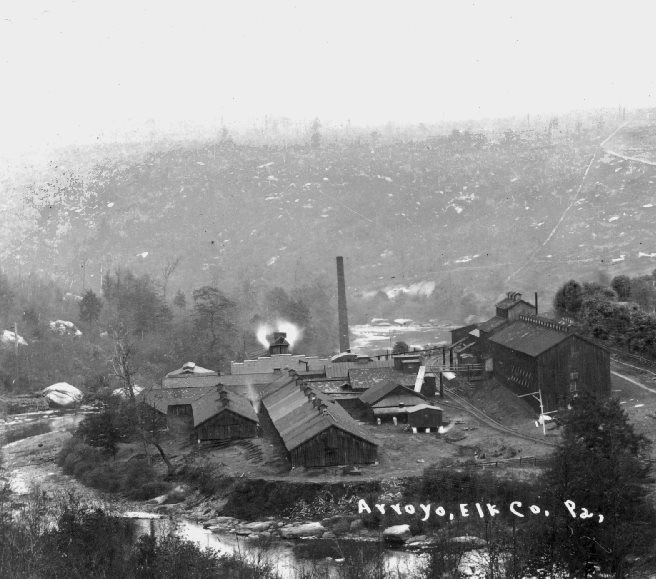

This is a photograph of the tannery at Arroyo, in Elk County, PA. This image is from around 1910, the height of the hide tanning era. Notice the denuded slopes behind the tannery. The river in front of the tannery is the Clarion.

After J.T. Rothrock visited in the late 1800s, he told his wife that only two words came to mind to describe the Clarion – desolation and abomination.

Consider the environmental impacts of this process. First, market hunters slaughtered the bison. Next, “bark peelers” cut all of the hemlock. It has been estimated that one tannery alone used 100,000 cords of hemlock bark from an estimated 400,000 trees over its 20-year history. Finally, they dumped all of the waste into pristine rivers and streams – lime, tannic acid, flesh, and hair.

Of course, I have ignored the social and cultural costs of this process. The bison were slaughtered not only for their hides. They were slaughtered as a way to control the remaining tribes of Plains Indians and to force them to reservations.

The forests of the Pennsylvania Wilds were completely obliterated during this era (post Civil War through early 1900s). Finally, at the turn of the century, Joseph Trimble Rothrock began taking his wagon through these devastated forests to photograph the wreckage. He returned to Philadelphia and gave lantern slide shows showing the “city people” in the east the extent of this ruination.

Through his efforts (and those of his acolytes such as Gifford Pinchot) the public finally forced the state into creating a forest bureau (now part of Pennsylvania DCNR) and a school of forestry in Mont Alto. Acquisition of these cutover lands by the state would soon follow, beginning over a century of restoration. The result of this effort is millions of acres of state forest in Pennsylvania, one of the world’s largest FSC certified sustainable forests.

The federal government has played a role in this restoration, as well. When the U.S. Forest Service first established the Allegheny National Forest in western Pennsylvania, locals ridiculed the land purchased as the “”Allegheny brush-patch.”

This final image is one of my own of the Clarion today. Arroyo is now part of the Allegheny National Forest. A section of the Clarion that crosses the national forest is now designated as a National Wild and Scenic River.

Let that soak in for a minute. In about a century, the Clarion has gone from “desolation and abomination” to “wild and scenic.” That recovery is due, in large part, to the efforts of the U.S. Forest Service and the PA DCNR Bureau of Forestry.

Now, virtually all of the land in the region is public (national and state forests), the only way this devastated region would have ever recovered.

The threats remain, however. The land purchased for the Allegheny National Forest, in many cases, only included surface rights. With the fracking boom, the forest has become riddled with active wells and pads. State forests have been opened to oil & gas development. Yet, with a recent change in administrations, there is hope that this too will be addressed.

This is the lesson that I take away from my studies of conservation history. Man’s rapacious, insatiable greed is inborn and indelible. Greed is an inexorable force, relentlessly searching for the tiny cracks where our attention wanes. Without the rule of law, and never-ceasing vigilance by we the people, man inevitably slides back into the dark abyss.

We have proven, time and time again, that we can change this world for the better. We will have to prove this again and again if this world is going to survive.

Man’s rapacious, insatiable greed is inborn and indelible. Greed is an inexorable force, relentlessly searching for the tiny cracks where our attention wanes. Without the rule of law, and never-ceasing vigilance by we the people, man inevitably slides back into the dark abyss.