A bird person may live next door, date your daughter, or drink a beer with you after work. You won’t know. Bird people are anonymous and invisible, remaining transparent unless outed by their binoculars, bird feeders, or the I Brake for Birds! sticker on the Isuzu in the driveway. Bird people are everywhere yet nowhere. Bird people are everyone yet no one.

I am a bird person.

To know more about bird people, let’s begin with a definition of who they are or aren’t. Simply put, bird people find their way to nature through wild birds. We feed birds, garden for birds, photograph birds, and watch birds. We collect bird books, photographs, and sounds, and some of us collect the names of the birds we have seen on a list.

Except for the shared interest in birds, little else is common among bird people. Although we number in the tens of millions, we are not a cohesive, delineated group. While other recreations have sharp edges and defined borders (you become a hunter the day your dad buys you a gun and a license), there is no single act that welcomes you to our bird fraternity. Our recreation is amorphous, porous, and pliable. Each bird person negotiates an individual relationship with both the resource and the recreation.

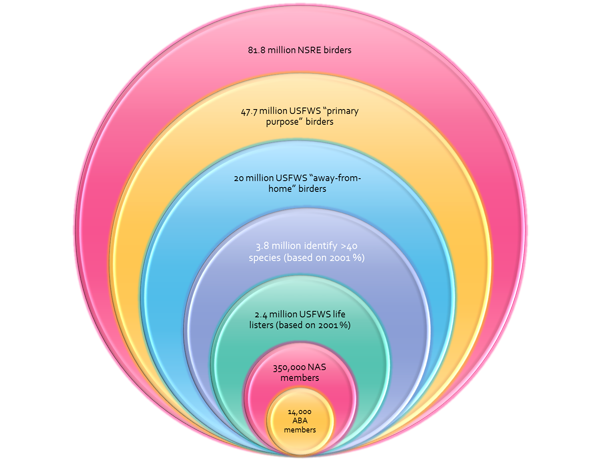

We count hunters and anglers by licenses sold. How do we count bird people? Poorly, I am afraid. The most commonly quoted survey is from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) titled Birding in the United States: A Demographic and Economic Analysis. According to the agency, in 2006 there were 48 million people in the U.S. age 16 or older who watched, fed, and/or photographed birds. Relatively equal numbers of men (46%) and women (54%) participated. Almost 42 million watched, fed, and photographed birds around the home, with around 20 million traveling away from home to enjoy birds (an increase of 8% over the 2001 survey).

The USFWS uses a conservative approach by limiting the survey. The agency is interested only in those who either closely observe birds around the home, or who take trips more than one mile from home for the primary purpose of watching, feeding, or photographing birds. Incidentally seeing a hummingbird while mowing the yard is not considered “watching.” Even so, this definition of bird people encompasses 21% of the American population, or 1 out of every 5 Americans. For comparison, the PGA estimates that there are 27 million golfers in the U.S., marginally over half of those who find their way to nature through birds rather than birdies.

The USFWS is not the only organization counting bird people. The most conservative (i.e., lowest) estimates are from the Outdoor Industry Association and their Outdoor Recreation Participation Report. According to the OIA and its Outdoor Foundation, 14.4 million American watched birds more than 1/4 mile away from home or a vehicle in 2008. In the same year over 24 million Americans watched wildlife away from home and car.

The USFWS counts both home and away from home watching, so the discrepancy in estimates is obvious. Yet I am comfortable with the USFWS 20 million watching birds away from home compared to the OIA 14.4 million. When counting bird people, close is as good as it gets.

Finally we have the National Survey of Recreation and the Environment (NSRE) to consider. I have worked with this survey for years, and I am comfortable with what it can and cannot provide. The NSRE offers the broadest view of recreation, and therefore I believe that their estimates are most accurate in delineating the softest edges of a given recreation. According to the NSRE, there are over 81 million American who watch birds, no matter how casually. Rather than considering this an estimate of a defined population, I would prefer treating this more as a potential. I do not believe that the vast majority of these 81 million Americans consider themselves to be birders or birdwatchers, but nevertheless they are finding their way to nature (no matter how circuitous the route) through birds.

Let’s summarize. There are over 80 million bird people in the U.S., according to the NSRE. Around 40 million closely watch, feed, and photograph birds around their homes, and between 15 and 20 million travel away from home to see birds. In addition, the three surveys show this to be a growing population. The bird people are on the move.

Why does this matter? For many of us, it doesn’t. But for those who are interested in organizing, marketing to, or understanding bird people, the numbers matter. Here is an example (carried forward from my most recent article on the American Birding Association). Currently the ABA has around 14 thousand members. Using the most conservative estimate (the OIA), this membership represents around a tenth of a percent of the traveling bird people in the nation. That’s right; one tenth of one percent! With 350 thousand members, the National Audubon Society does no better than 2.5% and these members are hardly all attracted to Audubon by birds. In both cases, memberships have been declining. How is it that bird people are growing while bird groups are shrinking?

Bird people are not just birders or birdwatchers. Bird people are diverse, and their interests diverge after the initial attraction to birds. ABA and Audubon have lost sight of the bird people, and have remained content to carve out what each has believed to be a competitive niche. The Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology (CLO) took a different tack with eBird, and the results have been (in my opinion) spectacular. Evolution has both winners and losers.

In the case of the ABA, their niche (the most avid of the birders) has evolved at a more pronounced rate than the group itself. The ABA is an eight-track tape, and the niche is buying iPods. Though ABA has toyed with new technologies (PEEPS and Ted Floyd’s use of Twitter), the organization’s leadership still views the recreation through tired, old eyes. Compounding the problem is that ABA is offering potential members less than in the past, and the little that is being provided is dated. Why should anyone be surprised that members are slipping away?

Economics 101 – if your market is growing, and your share is shrinking, you change. The alternatives are to close shop, or to be content with diminishing market share. I have no idea what will happen with ABA (or Audubon, for that matter), but both have fairly simple choices to make. The numbers are real, and the bird people are on the march.

Lead, follow, or get the hell out of the way.

Ted Lee Eubanks