Panels and signs are interpretive furniture, accouterments added to the interpretive space out of an ill-conceived sense of obligation and custom.

Interpretive signs are dead letter files where good messages go to die.

Media are faddish and ephemeral. The half life of any medium has been reduced in this digital age (will anyone enjoy Gutenberg’s run ever again?). What’s in today (Snapchat) evaporates tomorrow (Myspace).

Yet, interpreters hang on to media well after their shelf life has expired. Campfires, anyone? Why?

Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results…Albert Einstein

Consider the celebrated interpretive panel or sign. No park, museum, or trail is without them. Interpretive signs are de rigueur, a detail demanded by interpretive etiquette. But what do we know about this medium’s efficacy? Do these resin-infused planks actually work?

The research on interpretive panels is admittedly sketchy. Most of the writing on signs and panels is from the agencies trying to convince themselves of their utility. Cole1 found that visitors spend no longer than 25 seconds reading the text on an interpretive sign. In comparison, the standard radio ads runs about the same length, 30 seconds.

Thompson and Bitgood2 studying visitors to the Birmingham Zoo, reported that,

…signs of 30 words resulted in 15.15% readers; 60-word signs had 14.88% readers; 120-word signs, 11.33%; and 240-word signs, 9.73%.

Exactly what would (or could) you say in 30 words? Yet, the more words on the sign, the less people are willing to read it. A sign of 120 words is common in the interpretive world, but by going to that much text you lose a third of your audience. And, remember, even in the best of circumstances (30 words), 85% of the zoo visitors didn’t read the signs at all.

Hughes and Morrison-Saunders3 found that,

…while the trail-side interpretive signs provided no additional improvement in visitor knowledge, there appeared to be a positive increase in the perception of the site as providing a learning experience.

The Hughes & Morrison-Saunders study from Australia, I suspect, points at the reason. As they reported, with signs there appears to be a “positive increase in the perception of the site as providing a learning experience.”

Interpretive Furniture

Why do we continue to spend thousands on a sign that virtually no one approaches, no one reads, and, for the few that do take the time to read the content, there is virtually no learning experience or improvement in visitor knowledge? Panels and signs are interpretive furniture, accouterments added to the interpretive space out of an ill-conceived sense of obligation and custom.

Interpretive panels are furniture, accouterments added to the interpretive mix out of a blind sense of obligation. An interpretive sign is like a settee or a couch. Such furniture is required by a living room to make it living. The fact that no one actually sits in a settee is irrelevant; its presence is sufficient to bestow credibility on this space dedicated to a particular purpose. Without a couch, or an armchair, or a settee, the space simply cannot be for living. And, without interpretive panels, a park or trail simply cannot be for learning.

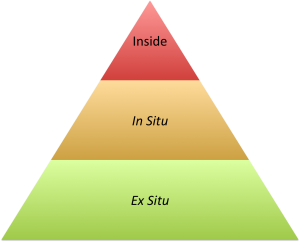

In guerrilla interpretation, we relegate all interpretive media to three general classes that are focused on specific audiences. First, there are media and messages that are focused inward. An example is when a nature center publishes a newsletter for its supporting members. The message are aimed at an inside or internal audience, and engagement is limited to those presumed to be already engaged. Virtually of the engagement efforts of professional organizations such as the National Association for Interpretation (NAI), for example, are for inside engagement.

The next class of media (and messages) are aimed at the in situ audience, those actually visiting the park, museum, or nature center. Most traditional interpretation is in situ. After all, Freeman Tilden wrote for National Park Service interpreters servicing visitors to the national parks. Engagement is haphazard (since visitors do have the right to chose), and restricted to those that (1) actually take the time to visit, and (2) actually take the time to read, view, or listen to the interpretation. Engagement is admittedly more expansive than media and messages that are internal, but still limited when compared to the general public.

The final class or group of media and messages are ex situ, and target the external public. The external market is certainly the most significant, but this audience also has the most tenuous connection to and interest in the park, museum, or trail being interpreted. Yet growth is dependent on reaching this audience (internal and in situ audiences are already engaged). Equally important, many of the factors that impact the sustainability of a park, museum, and trail (funding, political will) depend on the interests of the general public.

In guerrilla interpretation, we prioritize our interpretation based on potential audiences. Those media that are capable of reaching across these audiences (internal, in situ, ex situ) have a higher return on investment and thus a higher priority than those that do not. A membership newsletter has a low return based on audience size, while a blog or website can reach from the membership to the general public. An interpretive sign is limited to an audience that actually makes the investment in a visit, while a smartphone app, such as Trails2go, can reach from those who visit to those in the general public that are only toying with the idea.

All is not lost for the cherished wayside exhibit or interpretive sign. Static interpretive enhancements (interpretive platforms) can be improved. Placement (traffic points, on trail), bright colors, high imagery, content chunking, and low word counts are traditional ways to increase the use of interpretive panels.

But panels can also be guerrillized. Otherwise, interpretive signs are dead letter files, places where good messages go to die. Begin with the notion that while your messages may be lasting (you certainly would like for them to be), your interpretative media and platforms are transitory. A guerrilla interpreter works to make sure that the messages are durable, not signs. Why would you ever want to install a sign that will last 15 or 20 years? Will you not have something new to say over those decades?

Message freshening is particularly important in facilities and sites with significant repeat visitation. Rather than investing in signs that will outlast your career, install frames and rotate signs on a regular basis. New digital printing techniques offer the guerrilla interpreter a wide array of materials that can be used to create signs at a fraction of the cost of the traditional high-pressure resin or metal signs. Signs can be interlinked with the broader interpretive system through bar codes, QR codes, Clickable Paper, beacons, etc. Upload the sign designs as PDFs to your website, making them available to a broader audience.

Interpretive platforms such as signs and wayside exhibits are a low priority in guerrilla interpretation. Cost is high; return on investment is low. But, for those who are committed to these archaic platforms, be sure that they are guerrillized to broaden the audiences they potentially reach. And, keep the cost low. Standardize design. The notion of investing $2000 or $2500 in a single sign that few will read is difficult (impossible, really) to justify, guerrillized or not.

Cole, D.N., Hammond, T.P. and McCool, S.F. (1997) Information quantity and communication effectiveness: Low-impact messages on wilderness trail-side bulletin boards. Leisure Sciences 19, 59–72.

The data from this study were part of the first author’s master’s thesis

in psychology at Jacksonville State University.

Hughes, M.J. and Morrison-Saunders, A. (2002) Impact of Trail-side Interpretive Signs on Visitor Knowledge. Journal of Ecotourism Vol. 1, Nos. 2&3,.