The BP/Deepwater Horizon/Transocean/Halliburton farce continues. Farce is a poor choice of words, since a farce, in the theatrical sense, is humorous. The Gulf gusher is not farce, or funny. It’s despicable.

Birds have taken front stage in this disaster, at times overshadowing the loss of human lives. The images of birds floundering, drenched in a coppery gelatin ooze, are gut-wrenching. No, we shouldn’t forget the eleven men killed in the initial explosion. Yet I believe it human nature to reach out to those creatures that are helpless in their own right. I suspect that the media will continue to stream the grim images of the dead and dying birds

Good. The world needs to see.

As the gusher continues to blow its toxic mix into the deeps of the Gulf, the toll is mounting. We have all seen the glassy eyed brown pelicans, cormorants, gulls, and terns as they convulse on the beaches. But what does the average Joe really know about these birds, or the whales, dolphins, turtles, manatees, fish, crabs, oysters, and such that are equally vulnerable? The public knows only what it can see. If a bird is oiled, washes to a beach, and then is photographed by a press generally restricted from the area, it counts. The rest, the 99.9999% that never surfaces, is imaginary. A dead bird, fish, turtle, or whale out of sight is out of the public’s mind.

Here is what is at risk, what is dying as I write these words.

Waterbirds is an appropriate term for many of these coastal birds (I avoid the word species since it depersonalizes them). They breed, nest, feed, preen, loaf, forage, hide, display, and fly over and around these waters. The two, water and birds, are inextricable. Oil in water means oil on birds.

This is a tricolored heron, once called (much more appropriately) the Louisiana heron. Scientist tend to squeeze the life out of bird names. Least sandpiper. Lesser yellowlegs. Black tern. Red knot. Where is the magic? Where is the poetry in these names?

This heron is neck-deep in the waters of the Laguna Madre. The city of South Padre Island discharges fresh water from its waste water treatment plant near their convention center, and this spot has become popular for birds and birders. Birds such as this heron need fresh water to drink and bathe in, and in the hypersaline Laguna fresh water is hard to find.

Remember that point. All water is not equal. Some birds have enlarged salt glands that allow them to actually drink salt water. Some tolerate brackish water, and some demand only fresh water. All die when their preferred water is fouled with oil.

Look closely into this heron’s eyes. This is a living, breathing, pulsating creature, a unique individual, who, like tens of thousands of its kind, is now looking down the barrel of a gun. At the turn of the last century herons and egrets were decimated by hunters who shot them for their plumes. A feather or skinned bird atop a woman’s hat was in vogue then. Early conservationists such as Theodore Roosevelt, George Grinnell Bird, and Frank Chapman began the Audubon Movement to stop the slaughter. The guns have been silenced, but not the death.

Roosevelt conserved over 230 million acres in his nine years in office, including the first 51 bird reservations (now national wildlife refuges). Many of the earliest refuges are along the Gulf coast. How ironic that these same refuges are now threatened by a menace unknown in his time (although he did have the foresight to break Standard Oil into pieces).

Roseate spoonbills were not prime targets of the plume hunters since their feathers fade. The brilliant pink of a spoonbill is from the crustacea they filter out of the rich Gulf waters. But since spoonbills nested in the same rookeries as the other herons and egrets, their young were lost as well when the hunters came. Over the past century these waterbirds have begun to slowly recover from the millinery slaughter, yet they now face another threat. We have shot them, drained their marshes, and now pollute their waters.

Here is another egret you should know – the reddish egret. The reddish is the egret of the immediate Gulf, rarely ranging any distance inland. Audubon estimates that this bird has a continental population of around 12,000 (no more than 70,000 globally). At this moment these birds are nesting along the coast, with the next generation not yet able to fly. During the winter these egrets aggregate in large feeding flocks in the Laguna Madre of south Texas. What if the oil has shifted there? What about the whooping cranes that return to the central Texas coast in October? What about the redheads that winter in the Laguna, estimated to be 90% of this duck’s entire world population?

The whooping crane is not the only endangered species that winters along the Gulf coast. The piping plovers that breed in the Great Plains winter here as well. In fact, virtually all of the world’s population winters between Florida and Texas.

These birds feed along the beaches and sand flats, spending as long as 8 months gorging on interstitial organisms like polychaetes (worms in the sand). What if this sand is oiled? What if their food supply has been destroyed? Shouldn’t we have thought about this before poking a hole 5000 feet deep in the Gulf? How could the federal government have exempted this well from assessing the potential environmental impacts?

In this gusher (please, this is not a spill) oil permeates the water column. Even the sheen on the surface matters.

This black skimmer at the top of the page does as the name implies. The bird skims the surface of the water with its lower mandible extended into the water. When it feels a small fish, it quickly slams the bill shut. But in oil? What if there are no small fish to skim?

Eventually, the damage will be assessed, and we will begin the inane discussion about the dollar value of what has been lost. Let me ask a simple question. How much is your pet worth? How much would I have to pay you for little Fluffy? I have three cats, and I would never place a value on their lives. The joy they bring to my life is beyond a price.

I value birds in the same way. No sentient human on this planet has lived a life apart from birds. They are with us every day of our lives. We see them soar while driving to work, and we hear their songs while we barbecue in the backyard. Birds are ever present, and the most direct path for humans to find nature.

No, I will not tell you what a bird is worth. But I can tell you the economic value of watching them. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, birders spend over $35 billion annually in this country. Yes, that’s billion with a “b.” Of that staggering amount, over $12 billion is trip related, with the remainder ($23 billion) going to equipment and supplies.

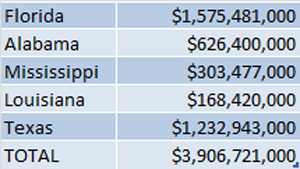

Here is how these expenditures break out for the Gulf states:

As you can see, wildlife viewers in Gulf coast states spend nearly $4 billion annually. Of course, not all of this is spent in coastal counties and communities. But Gulf birding is decidedly coastal, therefore it is safe to presume that the majority of the dollars are being at least generated by an interest in coastal birds. Most of the Gulf coast communities lack the retail facilities to adequately capture the sale of equipment and supplies, but certainly the expenditures for food and lodging stay along the coast. Even a conservative assessment would still credit birding with contributing hundreds of millions of dollars to the coastal Gulf.

But gross expenditures do not tell all of the story. The Gulf may be home to the American petroleum and petrochemical industries, particularly the segment of the Gulf between Corpus Christi and Baton Rouge, but one visit to this region will show you that most of that wealth goes somewhere else. Port Lavaca, Palacios, Bay City, Freeport, Clute, Texas City, Baytown, Sabine Pass, Port Arthur, Groves, New Iberia, Morgan City, Houma, and Thibodaux; wander through these coastal communities and follow the money. Where are the billions being earned annually by these immense companies? Why are these coastal communities so downtrodden and poor?

Simple. The dollars leave town. Yes, they do collect in places like Houston, but in general the coast itself is a plantation economy. The impact of the revenues that come from birding, fishing, hunting, and other types of recreation is therefore heightened in these otherwise depauperate communities. Now even this is threatened.

President Theodore Roosevelt, our first and greatest conservation president, said that “the nation behaves well if it treats the natural resources as assets which it must turn over to the next generation increased; and not impaired in value.” In the Gulf of Mexico we have not come remotely close to following his lead. We have drained the swamps, filled the marshes, channelized the rivers, dredged the harbors, polluted the waters with agricultural runoff and urban waste, and now we are suffocating a coast already on life support.

The Gulf coast has value if the birds have value. The coast has worth if its people have worth. For far too long this part of America has been servile, its people content to gather up the scraps from the master’s table. Edward Abbey said “God bless America. Let’s save some of it.” I agree. Why not start with the Gulf?

Ted Lee Eubanks

Galveston, Texas

12 June 2010