In the weeks since the eruption of the Gulf gusher, criticism of the administration and the president has been muted. There have been no marches on the Capitol, no insurrection in the Gulf. In fact, the only civil disobedience has come from BP.

For example,

- The freedom of the press (an unambiguous 1st Amendment right), has been continuously abridged since 20 April 2010. Journalists have been detained and harassed, swaths of the Gulf have been cordoned off from the public, and BP has hired its own “reporters” to obscure the truth.

- Independent scientists have been reduced to begging for a chance to collect critical baseline data from the gusher. BP and the administration continue to stall approval.

- We have learned that there are over 27,000 abandoned oil and gas wells in the Gulf, many dating to the 1940s. More than 1,000 “temporary” wells have lingered in regulatory limbo for over a decade.

- BP, the very company responsible for the oil spill that is already the worst in U.S. history, has purchased several phrases on search engines such as Google and Yahoo so that the first result that shows up directs information seekers to the company’s official website.

- The US Fish and Wildlife Service has admitted that they approved the original Deepwater Horizon risk assessment since they estimated the chance of a catastrophe at less than 50%. Yet this same agency is working in close collaboration with BP and Entrix (BP’s environmental consultant) on the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA). “If they pay the bills, they’re welcome at the table,” said Peter Tuttle, an environmental contaminant specialist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

To be fair, the Republican opposition has countered every move the administration has proposed. Texan Joe Barton wins the prize with his “I do not want to live in a country where any time a citizen or a corporation does something that is legitimately wrong, is subject to some sort of political pressure that is, again, in my words, amounts to a shakedown. So I apologize” wackiness. But I expect the Republicans to be loony when it comes to the environment. My concern is for our guy, this president, and his administration. This is his watch, and to date his response (or lack of) has been deplorable.

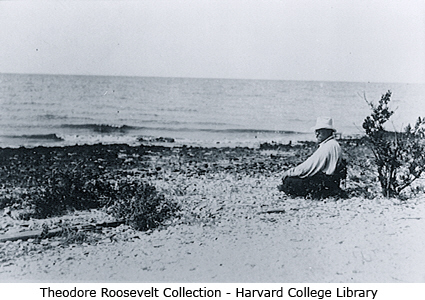

Teddy believed that he could rally the public to his side, and he rarely failed. If he felt mounting opposition within Congress (often from his own Republican party) he would hit the rails to tell the people his side of the story. Teddy understood that he could never get too far ahead of the public. I cannot believe that the public in the early 1900s understood conservation any better than us today. But they believed in the president, and knew that his conservation campaign would benefit all Americans, including future generations. In the end no president left his mark on the American landscape more clearly than Theodore Roosevelt.

I see nothing clear about this president, and he has offered nothing riveting or inspirational related to the Gulf that our citizens can hold on to. The Gulf fiasco offers a revelatory moment, an epiphany, when the interests of the public are starkly defined. The Gulf is a war, and the administration is still hoping for appeasement.

Why? Why aren’t the president and his administration attacking the gusher with force and gusto? Why aren’t outraged Americans spilling into the streets? Do Americans have a clue as to the true impacts of this disaster?

No, they don’t. In fact, I am not certain that most Americans even know where the Gulf is located. According to a Roper/National Geographic poll after Hurricane Katrina (and the around-the-clock media coverage), “nearly one-third of young Americans (ages 18 to 24) polled couldn’t locate Louisiana on a map and nearly half were unable to identify Mississippi.” Six in 10 could not find Iraq on a map of the Middle East. Why should I believe that more could locate the Gulf of Mexico?

Americans are semantically (as well as geographically) challenged. We are asking our neighbors to apply terms and concepts such as biodiversity, ecology, and food chain to the Gulf of Mexico when they haven’t yet seen or touched it in their own backyards. Many of these words have also become adopted by marketers, transforming critical scientific language and concepts into cheap slogans and squishy labels.

Sustainable is one of those squishy words (like eco, green, and ethical) that is a manipulatable modifer. Slap one before a word or phrase and presto! your product or service is sanctified. Several years ago Wired Magazine wrote about Patrick Moore, one of the Greenpeace founders. Today he owns a consultancy and often works in direct opposition to environmental organizations. A recent opinion piece on his webpage is titled How Sick Is That? Environmental Movement Has Lost Its Way. He is considered by some to be an eco-traitor.

Or what about eco-friendly Spandex, or eco-sexy dating? A few years ago I accompanied Texas Governor Rick Perry on a quick trip to Dallas and Houston to announce a new project along the Trinity River. I had been hired by the state to compile an assessment of eco-tourism opportunities in the region. As he introduced me in Dallas, he concluded by calling me an expert in eco-terrorism. The crowd laughed, and I assumed a simple slip of the tongue. However, he went on to repeat the mistake in Houston. Toe-mah-toe or toe-may-toe, eco-tourism or eco-terrorism, what’s the big deal when you’re governor?

When words like sustainable and eco become popularized, I get nervous. Perfectly good words often become diluted or bastardized when they reach the street. Queer (as in odd) is an example. Most of the green modifiers (like green itself) have become meaningless or indistinct. Heading the list is sustainable, the word that no one can define.

The Brundtland Commission tried. They defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Which (and whose) needs? Economic? Social? Ecological? Mine? Yours? The rich? The poor? One glance at America today should convince even the most blase observer that we have exceeded our economic capacity, our international policies have not proven to be sustainable, and we are going to hell in a hand basket in the Gulf. Does this mean that the U.S. is not sustainable? Of course not. In my mind, it means that the U.S., in its present configuration and on its present tack, isn’t sustainable. In sustainability, nothing is more important than knowing when to correct course.

Nothing, except for knowing what one is sustaining. Since my immediate interest is nature, let’s look at ecological sustainability. Exactly what are we sustaining? Do we try to sustain all of the parts, or only those that have value to us? Do we even know all of the parts?

In the Gulf gusher, the focus has been on megafauna such as brown pelicans, sea turtles, and dolphins. Nothing sells papers better than a dead baby dolphin on the beach. The press and non-profits report bird deaths like the weekly Viet Nam casualty reports once given by Walter Cronkite on CBS Evening News. But do we really know all that is being lost, all that is being eradicated? Are we only concerned with the obvious, with the dramatic?

Today is 6 July, and in about a week piping plovers will begin to arrive on the upper Texas coast. Around 75% of the world’s population of piping plovers winters along the Gulf coast. The remainder winter, in general, along the southern Atlantic coast.

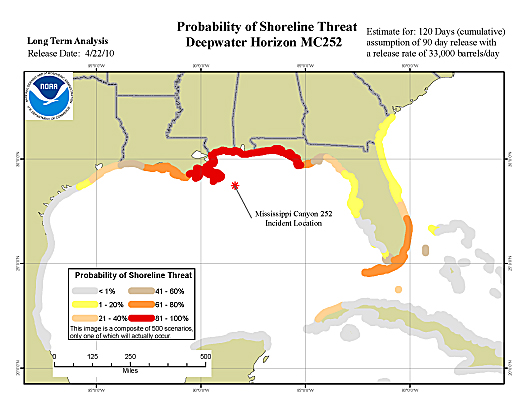

The most recent NOAA oil spill probability map shows a good chance of oil spoiling beaches throughout the plover’s winter range. There are fewer than 10,000 piping plovers left on the planet, and the bird is considered either endangered and threatened throughout its range. What makes a brown pelican intrinsically more valuable than a piping plover? Or what about a polychaete, part of the benthic infauna that shorebirds depend on for food? These are the segmented worms that live in the muck. Piping plovers spend much of their time foot-trembling in the soft sand, coaxing worms to the surface, then to the gullet. As worms go, so go shorebirds. As fish go, so go pelicans. Nothing about oil is good for worms or fish. Nothing about this oil is good for man or beast.

This brings me back to sustainability, my backyard, and John B.S. Haldane (hang with me, I know it’s a stretch). JBS Haldane is the biologist who said that “if one could conclude as to the nature of the Creator from a study of his creation it would appear that God has a special fondness for stars and beetles.” I would expand on Haldane and say that God must have an inordinate affection for life. Walk into your yard, any yard, and look. You will see only an infinitesimal fraction of what lives there, but even the obvious is overwhelming. The birds, mammals, and reptiles are apparent and exposed. But what about insects? What about all plants, not just the obvious (trees, shrubs, flowers)? What about nocturnal mammals and birds? And what about insects, including Haldane’s beetles?

What about damselflies? I photographed this damselfly in my yard this morning. On several occasions I have photographed ones infested with mites. You can imagine how small a damselfly mite must be. A couple of years ago I read a research paper about the parasites that live in the guts of mites that infest damselflies. That’s biodiversity, vividly illustrated in your own backyard.

Why does this matter? Because if you cannot see biodiversity in your backyard, that grasshopper in the cucumber blossom, how can you see it in the world? Within what context would you place biodiversity even if it’s under your own nose? Why should you care if you have never seen it, touched it, or known it? I know that this is a basic premise for Last Child in the Woods, but, no offense, the world cannot wait for 4th graders.

I have another yard, this one in Galveston. I live about 5 blocks from the Gulf of Mexico. Last week the first BP oil (tar balls) reached our beaches. The Gulf of Mexico is my extended yard, and I have seen, touched, and known its diversity for my entire life. Although I have spent countless hours in, on, and around the Gulf, I am still a neophyte, a dunce. I find peace knowing that what little I learn, what little I contribute, still becomes part of a grand encyclopedic saga.

Consider our friend Haldane one more time. In a famous study in Panama, 19 trees were “fogged” with insecticide and the dead were collected as they fell through the canopy. In this study, nearly 1,200 species of beetles alone were collected. Of those, 80 percent were not known to science. Extrapolation is dangerous, but studies of this type suggest a high estimate of the number of species that could exist on earth. The current best guess is around 10 million, the low around 2 million, but the number could be as high as 100 million species.

In truth, we have no idea how many species exist on this planet. Between 1.4 and 1.8 million have been named, but most experts admit that the total ranges between 2 and 100 million. Even a conservative estimate, let’s say 10 million, means that we currently have identified only 14% to 18%.

How many are left to be named in the Gulf of Mexico? Hell, we are still finding new named species there, a few big like whales. Once thought to be rare in the Gulf, in recent years pods of as many as 200 orcas have been found in the northern Gulf. How do you overlook an orca?

Easy. The Gulf is immense, the lookers minuscule. Below the surface both mystery and water deepen. We do not, we cannot, know all that is there, all that is being damaged, all that is being killed. Accurate loss estimates will take years, and will rely (as usual) on the effect rather than the cause. We will assume that piping plovers were harmed if we see the population drop over the next decade or so. We will assume that orcas were harmed if they vacate the Gulf. We will assume that brown pelicans were harmed if we wake up to find them gone, like in my childhood, from our beaches. We will assume that shrimp were harmed if shrimpers can no longer net them along the Louisiana coast.

What about those organisms that we haven’t seen, touched, felt, measured, or named? Without a name does a species not exist? What about individuals within a species (named or not), each striving to survive and reproduce in a world turned upside down? What about life, all life?

In the evening, when the heat of day fades, I relax on my porch in Galveston and watch the birds pass. The gulls, terns, pelicans, herons, and egrets stream over, though I see them only for a moment as they fly between beach and bay. For 116 years birds have passed over this house, and there has never been a time when the day broke without them. There is a continuity and a permanence in their presence.

The people of the Gulf also know they can be taken away by our greed, cruelty, ignorance, and indifference. Feather hunters, egg collectors, pesticide sprayers, wetland drainers, resort developers, and deep-water drillers have all left their lesions. One lesson still rings true – people value what they know, and they protect what they value. Too many people simply do not know nature, do not know that their backyard is a living, breathing organism of incomprehensible complexity and dazzling beauty. Many do not know even when their yard is the Gulf of Mexico.

Teddy Roosevelt, faced with the ruination of the heron and egret rookeries by feather hunters, had no trouble capturing the right tone and words.

And to lose the chance to see frigatebirds soaring in circles above the storm, or a file of pelicans winging their way homeward across the crimson afterglow of the sunset, or a myriad terns flashing in the bright light of midday as they hover in a shifting maze above the beach — why, the loss is like the loss of a gallery of the masterpieces of the artists of old time.

The Gulf is not a sewer, or a dumping ground, or an oil field, or a fund raiser. The Gulf is one of the masterpieces that Roosevelt is referencing, and he did his part to see it protected. Nature is a time machine, allowing us to share experiences with the past. The same birds that Teddy reported from the White House lawn a century ago can be seen today.

The challenges to nature also transcend time, and we are sharing one of those moments of clarity and revelation with Roosevelt. How would Teddy have faced the Gulf gusher? How can we follow his lead and lessons?

Here is one last Teddy story. Chapman and Boroughs came to meet with Teddy about the need to protect birds and wildlife in the Gulf, especially the rookeries. The discussion eventually shifted to the topic of federal lands and of sanctuaries. Roosevelt looked to an advisor, and asked about the legality of a president simply declaring these lands to be protected. A head nodded in the affirmative, and the president then made one of the most famous declarations in conservation history – I do so declare it. The AOU and Audubon then donated the funds to hire the first game wardens, men who served for little compensation and at great risk.

Roosevelt had brass. He understood that he had the public’s support to develop progressive conservation policy. In our time, we who know, we who believe, are responsible for garnering the public’s support (even beginning in our own yards). We cannot stay silent. We must wake from our sleep and challenge our neighbors, our fellow Americans, to rise to this occasion. Not all wars involve guns, bombs, and carnage. Wars can also be about beliefs, about sacred responsibilities. Our opponents have clearly defined their position, and drawn their line in the sand.

Have we?

Teddy said that “in a moment of decision the best thing you can do is the right thing. The worst thing you can do is nothing.” In our time, we must quit feeling sorry, sad, morose, horrified, and depressed and get back in the game. In your time, President Obama, it is your job to gut it up and follow Teddy’s example.

Ted Lee Eubanks

6 July 2010