MDG Advertising has come through with another insightful infographic. Thanks, MDG Advertising! Are you trying to decide between a smartphone app or the mobile web? Here are the numbers. Of course, you can do both. Our Trails2go app, built in Drupal, can be ported to the mobile web. But for those who want to choose, consider the information below.

Category Archives: Fermata

Guerrilla Interpretation – Interpretive Furniture

Panels and signs are interpretive furniture, accouterments added to the interpretive space out of an ill-conceived sense of obligation and custom.

Interpretive signs are dead letter files where good messages go to die.

Media are faddish and ephemeral. The half life of any medium has been reduced in this digital age (will anyone enjoy Gutenberg’s run ever again?). What’s in today (Snapchat) evaporates tomorrow (Myspace).

Yet, interpreters hang on to media well after their shelf life has expired. Campfires, anyone? Why?

Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results…Albert Einstein

Consider the celebrated interpretive panel or sign. No park, museum, or trail is without them. Interpretive signs are de rigueur, a detail demanded by interpretive etiquette. But what do we know about this medium’s efficacy? Do these resin-infused planks actually work?

The research on interpretive panels is admittedly sketchy. Most of the writing on signs and panels is from the agencies trying to convince themselves of their utility. Cole1 found that visitors spend no longer than 25 seconds reading the text on an interpretive sign. In comparison, the standard radio ads runs about the same length, 30 seconds.

Thompson and Bitgood2 studying visitors to the Birmingham Zoo, reported that,

…signs of 30 words resulted in 15.15% readers; 60-word signs had 14.88% readers; 120-word signs, 11.33%; and 240-word signs, 9.73%.

Exactly what would (or could) you say in 30 words? Yet, the more words on the sign, the less people are willing to read it. A sign of 120 words is common in the interpretive world, but by going to that much text you lose a third of your audience. And, remember, even in the best of circumstances (30 words), 85% of the zoo visitors didn’t read the signs at all.

Hughes and Morrison-Saunders3 found that,

…while the trail-side interpretive signs provided no additional improvement in visitor knowledge, there appeared to be a positive increase in the perception of the site as providing a learning experience.

The Hughes & Morrison-Saunders study from Australia, I suspect, points at the reason. As they reported, with signs there appears to be a “positive increase in the perception of the site as providing a learning experience.”

Interpretive Furniture

Why do we continue to spend thousands on a sign that virtually no one approaches, no one reads, and, for the few that do take the time to read the content, there is virtually no learning experience or improvement in visitor knowledge? Panels and signs are interpretive furniture, accouterments added to the interpretive space out of an ill-conceived sense of obligation and custom.

Interpretive panels are furniture, accouterments added to the interpretive mix out of a blind sense of obligation. An interpretive sign is like a settee or a couch. Such furniture is required by a living room to make it living. The fact that no one actually sits in a settee is irrelevant; its presence is sufficient to bestow credibility on this space dedicated to a particular purpose. Without a couch, or an armchair, or a settee, the space simply cannot be for living. And, without interpretive panels, a park or trail simply cannot be for learning.

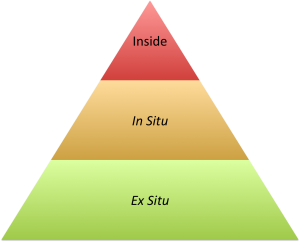

In guerrilla interpretation, we relegate all interpretive media to three general classes that are focused on specific audiences. First, there are media and messages that are focused inward. An example is when a nature center publishes a newsletter for its supporting members. The message are aimed at an inside or internal audience, and engagement is limited to those presumed to be already engaged. Virtually of the engagement efforts of professional organizations such as the National Association for Interpretation (NAI), for example, are for inside engagement.

The next class of media (and messages) are aimed at the in situ audience, those actually visiting the park, museum, or nature center. Most traditional interpretation is in situ. After all, Freeman Tilden wrote for National Park Service interpreters servicing visitors to the national parks. Engagement is haphazard (since visitors do have the right to chose), and restricted to those that (1) actually take the time to visit, and (2) actually take the time to read, view, or listen to the interpretation. Engagement is admittedly more expansive than media and messages that are internal, but still limited when compared to the general public.

The final class or group of media and messages are ex situ, and target the external public. The external market is certainly the most significant, but this audience also has the most tenuous connection to and interest in the park, museum, or trail being interpreted. Yet, growth (membership, support, visitation) is dependent on reaching this audience (internal and in situ audiences are already engaged). Equally important, many of the factors that impact the sustainability of a park, museum, and trail (funding, political will) depend on the interests of the general public.

In guerrilla interpretation, we prioritize our interpretation based on potential audiences. Those media that are capable of reaching across these audiences (internal, in situ, ex situ) have a higher return on investment and thus a higher priority than those that do not. A membership newsletter has a low return based on audience size, while a blog or website can reach from the membership to the general public. An interpretive sign is limited to an audience that actually makes the investment in a visit, while a smartphone app, such as Trails2go, can reach from those who visit to those in the general public that are only toying with the idea.

All is not lost for the cherished wayside exhibit or interpretive sign. Static interpretive enhancements (interpretive platforms) can be improved. Placement (traffic points, on trail), bright colors, high imagery, content chunking, and low word counts are traditional ways to increase the use of interpretive panels.

But, panels can also be guerrillized. Otherwise, interpretive signs are dead letter files, places where good messages go to die. Begin with the notion that while your messages may be lasting (you certainly would like for them to be), your interpretative media and platforms are transitory. A guerrilla interpreter works to make sure that the messages, rather than the signs, are durable. Why would you ever want to install a sign that will last 15 or 20 years? Will you not have something new to say over those decades?

Message freshening is particularly important in facilities and sites with significant repeat visitation. Rather than investing in signs that will outlast your career, install frames and rotate signs on a regular basis. Standardize and flatten design. New digital printing techniques offer the guerrilla interpreter a wide array of materials that can be used to create signs at a fraction of the cost of the traditional high-pressure resin or metal signs. Signs can be interlinked with the broader interpretive system through bar codes, QR codes, Clickable Paper, beacons, etc. Upload the sign designs as PDFs to your website, making them available to a broader audience.

Message freshening is particularly important in facilities and sites with significant repeat visitation. Rather than investing in signs that will outlast your career, install frames and rotate signs on a regular basis. Standardize and flatten design. New digital printing techniques offer the guerrilla interpreter a wide array of materials that can be used to create signs at a fraction of the cost of the traditional high-pressure resin or metal signs. Signs can be interlinked with the broader interpretive system through bar codes, QR codes, Clickable Paper, beacons, etc. Upload the sign designs as PDFs to your website, making them available to a broader audience.

Interpretive platforms such as signs and wayside exhibits are a low priority in guerrilla interpretation. Cost is high; return on investment is low. But, for those who are committed to these archaic platforms, be sure that they are guerrillized to broaden the audiences they potentially reach. And, keep the cost low. The notion of investing $2000 or $2500 in a single sign that few will read is difficult (impossible, really) to justify, guerrillized or not.

Cole, D.N., Hammond, T.P. and McCool, S.F. (1997) Information quantity and communication effectiveness: Low-impact messages on wilderness trail-side bulletin boards. Leisure Sciences 19, 59–72.

The data from this study were part of the first author’s master’s thesis

in psychology at Jacksonville State University.

Hughes, M.J. and Morrison-Saunders, A. (2002) Impact of Trail-side Interpretive Signs on Visitor Knowledge. Journal of Ecotourism Vol. 1, Nos. 2&3,.

Guerrilla Interpretation – All About That Media

We become what we behold. We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us…Marshall McLuhan

Imagery shapes our understanding and appreciation of the world around us. Once skills for the trained or talented (painting, drawing, photography), imagery, in the form of digital photography, is now in the hands of Everyman. There are 350 million photos posted on Facebook every day.

Images has taken the place of the written word in our post-literate society, replacing the words with logograms, symbols, and icons. With an unmatched immediacy, intimacy, and individuality, imagery is replacing extended discourse and explication with emotional shorthand. Using a much-abused proverb, in this post-literate environment, every picture tells a story.

Advertising, marketing, and media researchers have recognized the power of imagery for decades. Interpretation comes late to this recognition. For a guerrilla interpreter, imagery is the lingua franca, allowing us to reach across to a general public unfamiliar with the languages of nature, culture, and history.

The following is adapted from John R. Rossiter’s Visual Imagery: Applications to Advertising, in NA – Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 09, eds. Andrew Mitchell, Ann Abor, MI : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 101-106. My adaptation involves simply replacing advertising with interpretation.

Pictures have a demonstrable superiority over words when it comes to learning. A leading explanation of this superiority is Paivio’s dual-coding theory, which holds that pictures generally result in a visual representation as well as a verbal one, whereas words are less likely to result in the former. Long-term visual memory, unlike long-term verbal memory, appears to have virtually unlimited capacity, deteriorates very slowly, if, at all, and shows no primacy or recency effects.

[The order in which information is learned determines how reliably it will be recalled. The first item in a list is initially distinguished from previous activities as important (primacy effect) and may be transferred to long-term memory by the time of recall. Items at the end of the list are still in short-term memory (recency effect) at the time of recall.]

- Visual content warrants relatively more interpretive attention than verbal content.

- Use high imagery (more concrete) visuals rather than abstract visuals. The same applies to words. Low imagery words are more difficult to recall that high imagery words.

- Use color in visuals for emotional motivation.

- High imagery visuals work far better than “instructions to imagine.”

- The larger the illustration, the better.

- Seek attention-holding illustrations, not just attention-getting illustrations.

- Place the illustration where it will be seen before the headline and copy (i.e., content) are read.

- Attitudinal “wearout” should not be a problem with illustrations but they may lose attention, suggesting use of variations on a theme for broad interpretive strategies. Another strategy is to use imagery on a rotational basis, such as changing out interpretive exhibits and panels on a regular basis.

The following is a helpful infographic developed by MDF Marketing about the use of imagery. Granted, this infographic pertains primarily to advertising. Interpretation and advertising are faced with similar challenges, though. How do we most effectively communicate with our public? How do we best use the media to place information before our public in forms that will be accepted and consumed? To what types and forms of information is our public most receptive? How do we lead people to an action (in the case of advertising, to purchase)? How do we adapt our interpretive lexicon to include visual grammar?

Imagery is often treated as last-minute filler, an afterthought, in traditional interpretive planning and design. The interpretive plan is written, content is researched, and interpretive materials are designed before imagery is considered. The result is a generation of image trolls, scouring the Internet for free, unrestricted images in the public domain. Yet in this world of abundance, where billions of images are being posted every week, quality is one way to stand out and compete for attention.

Many researchers have agreed that only words and images are used in mental representation. Supporting evidence shows that memory for some verbal information is enhanced if a relevant visual is also presented or if the learner can imagine a visual image to go with the verbal information. One direct implication of Paivio’s Dual Coding theory is that pictures or concrete language (e.g., juicy hamburger) should be understood and recalled better than abstract language (e.g., basic assumption), a consistent research finding.

Guerrilla interpretation embraces imagery as a primary focus for interpretation. An entire interpretive schema can be constructed around a single image. Imagery gives us our most significant interpretive yield (pictures generally result in a visual representation as well as a verbal one, whereas words are less likely to result in the former), and therefore guerrilla interpretation elevates imagery to a position of primacy in the interpretive process.

Infographic by MDG Advertising

The Interpreter’s Eye – Macro Photography

Macro lenses are to close subjects what telephotos are to the distant. A macro lens magnifies a subject well beyond what the viewer would see in real life. The macro opens a window into the world that exists beneath our gaze.

I bought my first macro lens in the early 1970s. I clearly recall shooting my first roll of film with that Canon 50 mm macro, and how transformed I felt when I viewed the slides for the first time. Those slides of roses were the work of a photographer, I thought.

Little changed in the world of macro for the next couple of decades. The lenses were short, and the film slow. A 50 mm is fine for roses, but for insects, forget it. There is simply not enough magnification or shutter speed to do an insect justice.

All of this has changed in recent years. Digital cameras, VR (vibration reduction) lenses, and post-processing software such as Photoshop have transformed macro photography. For a photographic interpreter, this transformation is radical. We are now interpreting subjects that before we could only show with a hand-drawn illustration or describe with text.

Look at the eyes of the royal river cruiser at the top of this article. A dragonfly’s eyes have over 30,000 facets or lenses. A dragonfly can see in every direction, and its eyes are sensitive to all of the colors we see as well as UV. Macro photography allows me to show the opalescent dragonfly eye, and to place my viewer at the conjunction of art and science.

Now look at the thorax of this Rambur’s forktail. Notice those small balls or globs gathered there? These are water mites, parasites that affix themselves to damselflies and spend most of their brief lives glued to the sides of this tiny insect. A Rambur’s forktail itself is difficult to see without optical aids, but the water mites are only visible in a macro photograph such as this.

Technologies such as digital photography are expanding the possibilities for interpretation, but only if interpreters are skilled in their adoption and their use. Technological advances are of little use if the basic skills are lacking. For those with those skills and talent, however, this new age of digital photography is a godsend.

The Interpreter’s Eye

A snowy egret isn’t a rare bird. Nowhere along the Texas coast is this bird difficult to see. Snowy egrets are background birds.

Photographs of snowy egrets aren’t rare, either. Egrets are large, gregarious, and easy to see and photograph. New bird photographers, once they have disposed of the birds in the yard, often move to herons, egrets, and other long-legged waders.

The photograph of this common bird shown above isn’t an accident. The image is the product of the interpreter’s eye. An interpretive image differs from most in that it offers a number of different story lines to develop. An image of a snowy egret alone, stripped of any meaningful background, is a constricted platform. Yet, framed in this specific way, the snowy egret photograph can be used to explore the bird and its surroundings.

First, we could discuss the life history of the snowy egret. Notice the two hatchlings crouched behind the adult. This photograph is from a rookery, a colony where herons and egrets nest en masse. Rookeries are complex systems, with diverse members (herons, egrets, cormorants, anhingas) and predators such as the American alligator that I saw slithering through the duckweed underneath the trees.

Second, the flowering plant to the right of the birds is American elderberry (Sambucus canadensis). The photograph has been framed to include the elderberry flower. Elderberry fruit are used for jellies, jams, wine, and liquors. The stems of elderberries were once used as spigots for tapping sugar maples. An interpretive sign could just as easily focus on the elderberry as on the snowy egret.

Finally, the fact that the snowy egret isn’t rare is a story in itself. Admittedly, the snowy egret is one of the most common nesting birds in this rookery at High Island (no doubt the best known and most frequently visited rookery in Texas). Yet, in the late 1800s, this bird almost disappeared from Texas. Market shooting for the millinery trade decimated their populations in the U.S. By the late 1880s, over 5 million birds were being killed each year for their feathers.

President Theodore Roosevelt began protecting these birds and their rookeries when he established Pelican Island in Florida as the first wildlife refuge by executive order in 1903. Protection would be extended to Texas colonies in years to come. The fact that High Island is owned and managed by Houston Audubon Society is apropos given the importance of the original Audubon societies in bringing a halt to the trade.

The interpretive image is first seen through the interpreter’s eye. Interpretive photography is the skill of framing a subject in a way that invites an exploration of more than the subject itself. The stories that emanate from the background are often as important as the primary subject. The interpretive photographer crafts the image in a way that offers the interpreter a diversity of stories to tell and paths to travel.

![Should You Build a Mobile App or Mobile Website? [infographic by MDG Advertising] Should You Build a Mobile App or Mobile Website? [infographic by MDG Advertising]](http://www.mdgadvertising.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/should-you-build-a-mobile-app-or-mobile-website.png)

![It’s All About the Images [infographic by MDG Advertising] It’s All About the Images [infographic by MDG Advertising]](http://www.mdgadvertising.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/its-all-about-images-infographic_1000.png)