The weather heads salivated for days. Nothing provokes a Pavlovian response in weather geeks more than another storm of the century (How many are we allowed in one century?). I knew Pittsburgh to be in the path, but we glided into town with little trouble. Deplaning I watched the frontal system sweep the runway, and by the time we entered the terminal spitting rain and raging winds shook the building. Scheduled to speak in West Virginia the following day, I sprinted to my rental car and headed west toward the interstate. I made the mistake of following the directions dictated by my iPhone, and soon I left the interstate far behind and slid toward Appalachia on a narrow, serpentine two-laner.

While certainly no hurricane (I love how the weather heads trot out that analogy.), I decided that the rain, wind, darkness, a narrow road, and 60-year-old eyes did not blend well. I bailed early. Reaching I-76 (my route south), I navigated toward Cambridge, Ohio. I am not sure if I had previously heard of Cambridge, but I am certain that I never visited (To be honest, I still don’t know why I ended up in Ohio.). Situated at the intersection of two interstates, I suspected that I could find a hotel and restaurant along the highway. I exited the freeway at Cambridge and entered the American Everywhere.

James Kunstler characterized America as “ever-busy, ever-building, ever-in-motion, ever-throwing-out the old for the new; we have hardly paused to think about what we are so busy building, and what we have thrown away. Meanwhile, the everyday landscape becomes more nightmarish and unmanageable every year. For many, the word development itself has become a dirty word.” Cambridge, I found, is this everyday landscape. The town offered its handshake with Ruby Tuesday, Hampton Inn, McDonalds, and Pizza Hut. All were the same as at home; all were the same as found throughout interstate America. To Kunstler this is nowhere; to me it’s everywhere.

America is new, rootless. Americans share an impoverished sense of place. We have no Mecca, no Angkor Wat, and no Taj Mahal. American natives have special places, but we immigrants see little value in them. Consider the conflict over Bear Butte, South Dakota. To the Lakota this is sacred ground. To Sturgis this is a potential campground and parking spot for Harley riders.

Early conservationists believed that America’s specialness could be found in her landscapes. Theodore Roosevelt said that “There can be nothing in the world more beautiful than the Yosemite, the groves of the giant sequoias and redwoods, the Canyon of the Colorado, the Canyon of the Yellowstone, the Three Tetons; and our people should see to it that they are preserved for their children and their children’s children forever, with their majestic beauty all unmarred.”. For Roosevelt, what America lacked in ancient monuments and edifices it more than gained with her transcendent lands and wildlife.

Americans, however, are now becoming detached from this heritage, with these special places. Roosevelt warned that “the lack of power to take joy in outdoor nature is as real a misfortune as the lack of power to take joy in books.” How many Americans take joy in either? In 2004, a National Endowment for the Arts report titled “Reading at Risk” found only 57 percent of American adults had read a book in 2002. The Outdoor Foundation reports that over half of Americans “take no joy in outdoor nature,” with alarming numbers of children divorced from the outdoors.

Now, slipping into Cambridge, I confront the America devised by its marketeers. I see the America invented by global hucksters, their goods relentlessly hawked on the ubiquitous television. The McDonalds on the screen is the McDonalds in Cambridge. The Wal-Mart on television is the Wal-Mart in Cambridge. The streets signs, billboards, traffic lights, and facades are no more real in Cambridge than on the tube. This version of America, known by all, is fakery unleashed and unlimited. I can’t decide if I am in the Matrix or the Truman Show.

As a child I would visit my grandparents in Paris (Texas) several times a year. In that pre-interstate age (President Eisenhower, who initiated the interstate system, did not begin his presidency until 1953.), the roads invariably wended from downtown to downtown. My sister and I knew every hamburger joint and rest stop between Bryan and Paris. Even today I remember the sweet-and-sour lusciousness of the limeade in Sulphur Springs. Each town along our route had an identity, a character.

Now, your McDonalds is my McDonalds, your Wal-Mart is my Wal-Mart. Why leave home if all that is offered away is the same as in your neighborhood? Forget the family that once owned and worked in that Sulphur Springs hamburger and limeade joint, or the snow cone cart by the railroad track that my grandfather would take us by after work. What is more important to Everywhere America is that (1) everywhere is the same, and (2) everywhere is cheap.

One hotel is easily replaced by another (Hampton by Holiday Inn Express). One restaurant is easily substituted for another (Ruby Tuesday by Chiles). But what about that for which there are no substitutes? Would you replace Gettysburg with any Civil War site? What about substituting a pileated for the ivory-billed woodpecker, or a mourning dove for the passenger pigeon, or a penguin for the great auk? In a world of cheap throwaways and easy replacements, that which cannot be replaced is at risk.

Returning to my factory hotel I jotted a note on Facebook about Cambridge, a brief snippet asking “where the hell am I?” The responses came immediately. One friend wrote “heard of it. Dangerously close to my old stomping grounds and soon to be new stomping grounds. And yes, there’s really not much there!!” My heart sank (not really; I stopped for a meal and a bed). Then another friend sent the following: “You are near an excellent birding location! It’s called “the Wilds.” It’s a reclaimed strip mining area… The facility also has yurts for overnight guests. Very cool place and staff.” Soon another posted that “that area is full of special places…the Wilds being number one.” Humm, there seems to be a there there.

But how would you know if you bumped into Cambridge from the interstate? Like America, Cambridge is hidden by a shiny plastic wrapper. Only when you peel the layers back do you find the meat on the bones, the Hocking Hills, the Salt Fork State Park, and the Wilds. The American marketing machine sells gloss and I am interested in gristle.

How can we save that which does not exist for most Americans? Federal programs such as the National Heritage Areas and America’s Byways are selective and only touch on a few of these special places. Getting people into the outdoors is only a small part of the challenge. First, they need to know where to find the outdoors. Second, once there they need help in connecting to the land, its recreations, and its stories. Modern television marketing is delivered turn-key, without any requirement that you think. In the outdoors, the experiences are earned rather than gratis.

Finally, our special places need space. The American soul (as tangibly embodied in these places) is being squeezed from all sides, with what makes the American experience special being pushed aside for a marketeer’s version of the American story. American places need space in the American mind and in the American landscape. These are the American touchstones, special places with names and physical locations where we return to remind us of who we are, what we have accomplished, and how to navigate forward based on our past experiences.

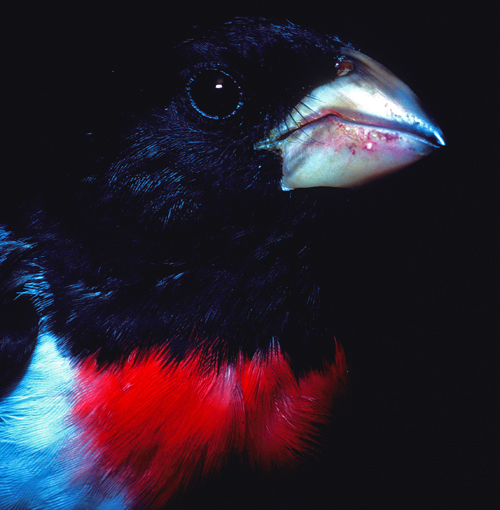

Isn’t this a critical aspect and appeal of birding? Each spring I return to the Texas coast to see the same birds that pass through the same special places such as High Island. With each day new migrants appear, northern parula followed by rose-breasted grosbeak followed by blackburnian warbler followed by yellow-billed cuckoo followed by least flycatcher. What could be more reassuring than the annual reappearance of birds that we exert absolutely no control over? As long as we protect their places, their cycle will continue. As long as we protect their places, our children and grandchildren will find the same inspiration and joy in this spring ritual that I have for the past four decades.

In the early 1990s I begin developing the first birding trail with Texas Parks and Wildlife. I remember being criticized by a group from Colorado that assured me that “real” birders did not need my birding trails. Perhaps “real” birders can find these special places, but the vast majority of the rest of us can’t. With initiatives such as birding trails, IBAs, and eBird places we are bringing America’s special birding places to the attention of the public and the officials guided by their sentiments. Birding trails are a celebration of birding places, those parks, refuges, and sanctuaries where we return to reassure ourselves that the world is still spinning and that the birds are still migrating.

America is adrift, stumbling forward with a road map drawn by shock-jocks and gas bags. When lost we tune in our favorite bloviator and ask for directions. Yet there is a real behind the unreal, a wonderful store filled with goodies behind the facade. If you want to know the American story, you must experience the American places. If these places are to continue to comfort, inform, enlighten, entertain, inspire, enliven, guide, and reassure us, then they must be given ample space in the American psyche. America, now more than ever, needs space for place.

Ted Lee Eubanks

4 Nov 2010