Skimming Huffpost on my IPad, I notice the story that Delaware Republican Senate candidate Christine O’Donnell has called evolution “a myth” and backed up her claim with the question: if evolution is real, “why aren’t monkeys still evolving into humans?” While isolated in Iceland last week [a grand place to get away; nothing is distracting in Reykjavik], away from the yapping heads, I thought about how partisanship in the U.S., while hardly new, has once again returned to its roots – base ignorance. Nothing motivates voters more than blind hate and mindless fury. I cannot imagine people more blind and mindless than those moved to passion at this moment like O’Donnell.

I have yet to hear a single word from the Tea Party or their kind that resonates with me. To be honest, I cannot imagine why anyone would want to expose such silliness in public. For the Western world the Age of Enlightenment centered on the 18th Century. What is forgotten is that the time preceding the Enlightenment, the Dark Ages, was a self-imposed devolution and backwardness. The Roman and Greek classical ages were temporarily lost not through a force of nature but through the force of human ignorance and religious myopia and corruption. The classics were restored to the West through the benevolence and enlightenment of Islam. I wonder who has our back now (forget Islam, by the way).

A multi-party system of government gives rise to partisanship, a natural outcome of competing ideologies vying for power. But what happens when the parties share a basic ideology? Rather than competing over grand ideas, the parties must battle over minutia. Grand philosophical debate is reduced to petty partisanship and ad hominum attacks. Welcome to our time, the age of microscopic people espousing nano ideas. Change in our age is not about transformation; change in our age is no more meaningful than a change of clothes or sheets.

Conservation has become distinctly partisan as well. Most environmentalists like me are liberal Democrats. Republicans oppose us not because of our ideas but because of our ideology. We embed conservation into a liberal social agenda, and support the party (the Democrats) who are more aligned with liberalism as a whole.

The result is that the Democratic Party presumes that our support will be freely given rather than earned. The partisan alignment of the environmental movement guarantees that the Democrats will ignore us while the Republicans will oppose us. We have convinced ourselves that the Democrat’s passive acknowledgement of environmental issues is better than outright Republican opposition. As a result Democrats are rarely blamed and Republicans rarely credited.

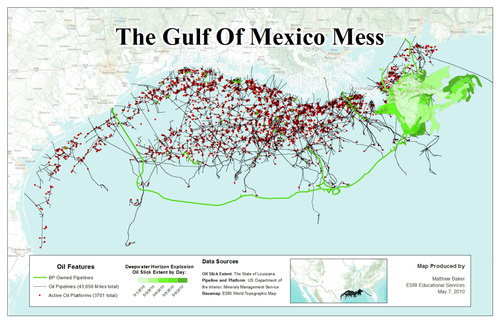

The Deepwater Horizon gusher is an act of man and therefore unlike Katrina, a natural phenomemon or act of God. The federal government had oversight responsibilities of the well from the outset. In this both administrations failed. The MMS cozied up to the industry it regulated in both the Bush and Obama years, and the USFWS permitted the well without an EIS during the Obama administration. Unlike Katrina, the Deepwater Horizon could have been prevented, and in this both administrations were negligent. With that said, we supported Obama because he promised change, not continuation of the disastrous policies and practices of the past. Blaming Bush for BP is as meaningless as blaming Clinton for 9/11. All Americans want to know is who’s on watch.

Where Katrina and BP are alike is in the political responses to the disasters. Simply go back and review press releases from both administrations during the early days of these events. I understand the fog of war, but why are the estimates of negative impacts always low balled? Why do administrations, no matter the party, always grossly understate the obvious knowing full well that the truth will eventually out? The Bush administration estimated that the war in Iraq would cost $50 billion to $60 billion; now the total cost is in the trillions. President Bush praised FEMA in the early aftermath of Katrina (“Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job”), and the final estimates of oil gushing into the Gulf exceeded early Obama administration numbers by orders of magnitude. How should we, the public, respond to such obvious errors or obfuscations? Oops?

Exactly what has the Obama administration accomplished for the environment that should earn our unquestioning support? Despite a clear majority in Congress, the administration failed to advance cap-and-trade. The America’s Great Outdoors initiative is palliative care (like the Last Child in the Woods campaign), long on meetings and talk but short on substantive change. As Frank Rich said during the early days of the BP gusher,

Obama was elected as a progressive antidote to this discredited brand of governance. Of all the president’s stated goals, none may be more sweeping than his desire to prove that government is not always a hapless and intrusive bureaucratic assault on taxpayers’ patience and pocketbooks, but a potential force for good.

I still believe in government as a potential force for good. I still believe that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. But I also believe, as did Jefferson, that “all tyranny needs to gain a foothold is for people of good conscience to remain silent.”

Early this summer I wrote an article about the environmental movement’s abdication of advocacy. An aspect of this surrender is the partisan alignment of the movement today. Advocacy should be focused on the issues and the cause, not on any particular party or power. For example, Martin Luther King found it necessary to split with President Johnson over the war in Viet Nam in his Beyond Viet Nam speech. This critical shift, while consistent with his cause, led to him to be ostricized by many who had previously supported him. President Theodore Roosevelt battled with his own Republican party over his progressive agenda, particularly conservation and public lands. No matter how vilified or disputed, they remained true to their beliefs and the causes.

The Gulf gusher has been a moment in time that begged for clear, unambiguous leadership and action. When Harry Truman faced a railroad strike that would have crippled the country, he responded by threatening to draft all railroad workers into the Army. Theodore Roosevelt used John Lacey’s new Antiquities Act to circumvent a recalcitrant congress and protect millions of acres of America’s heritage. Franklin Roosevelt closed the banks for a “bank holiday” to stop the hemorrhage that threatened to bleed the country even deeper into the Great Depression.

The BP disaster has been Barrack Obama’s defining test, that one event in time when a presidency is made or broken. Only at these critical moments can a president step outside of his or her political skin and lead the nation as an individual, a fellow American. The country forgave Roosevelt’s being caught off guard at Pearl Harbor because he and the nation he led ultimately won the war. Roosevelt honed in on the prize (victory) and swept away the conventions and structures of the past that kept him from that goal. In the Gulf this president has continued with the shopworn policies and agencies of the past, and has offered little in the way of a grand idea for the Gulf restoration beyond platitudes and promises.

Conservation and the environmental movement (not necessarily the same) should embrace a return to the nonpartisan advocacy of the past. Let me be clear – there are two forms of nonpartisanship. The first is to avoid all forms of advocacy, as seen with groups such as the Nature Conservancy. The polar opposite is an advocacy that believes that all should be held accountable, and that the basic tenants and beliefs of conservation must transcend (rather than ignore) the politics of the day. I care little for the former, but the latter is the advocacy that I embrace and promote.

Let’s return to the Gulf. Here the Obama administration has done little more than promulgate the mistakes and inefficiencies of the agencies and allies that he inherited. Where is the change promised just two years ago? Where is the bold, daring leadership that challenges the country to rise to this occasion, to be its best? The Gulf has been an America colony since the end of the Civil War. Wealth is extracted, with little returned. Isn’t the restoration of the Gulf and its people worthy of this president’s interest and investment?

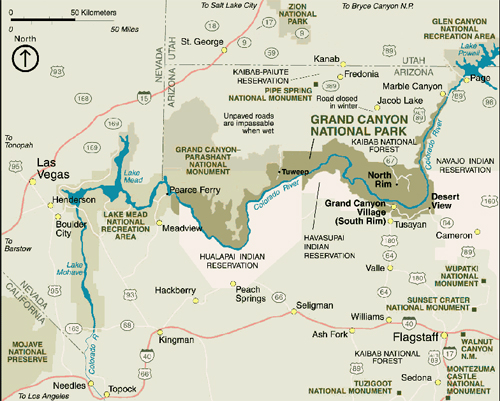

Here is where I would begin. No one disputes that a lot of oil lies untapped under the rocky floors of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans off the U.S. coasts. Yet drilling in these areas has been banned by Congress since 1982. Recently six U.S. senators from the states along the West Coast including Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein jointly introduced legislation to ban all future drilling along the Pacific shoreline. Notice that drilling rigs in the Gulf stop at the Florida Panhandle. Drilling is banned offshore of Florida as well. Why? Why are Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, along with Alaska, bearing the weight of coastal oil and gas production and refining in the U.S.? And if the Gulf is being sacrificed so that others in the U.S. can drive in their SUVs to their oil-free beaches or ship their crops to foreign markets, shouldn’t the impacts to the Gulf be mitigated for with revenues from these economic activities? Shouldn’t the federal government be investing these revenues back into the Gulf states to build local capacity, expertise, and the research necessary to respond to future spills and future dead zones? Shouldn’t national environmental organizations be aiding local groups and institutions in developing the financial and human resources that would aid this capacity building, rather than sucking even more funding from the Gulf to New York and Washington?

To date reinvestment has not been the trend. Washington-based Defenders of Wildlife has received a $216,625 noncompetitive contract from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for a seabird survey in the Gulf. Manomet, based in Plymouth MA, has received a similar grant to survey shorebirds. Bird cleaning funds have gone to three out-of-area firms. Local universities have been unused, and volunteers have been kept on the sidelines. The issue is not whether or not Defenders and Manomet are well-meaning, worthwhile organizations (they are). My concern is how Gulf environmental interests, as limited as they are, have been effectively locked out by those who should have their best interests at heart.

Did the USFWS believe that Defenders is better qualified to count seabirds than Van Remsen’s LSU, Frank Moore’s Southern Mississippi, Texas A&M, or the Gulf Coast Bird Observatory? Is Manomet more familiar with the shorebirds and their habitats along the Gulf than local birders and scientists that have been surveying shorebirds here for decades? Why aren’t the national environmental organizations insisting on local involvement in the NRDA and environmental assessments, or are they too busy trying to snatch their own slice of the pie?

For those along the Gulf, the refrain is familiar. Funds dedicated to those with the least often end up in the hands of those with the most. For example, five years after the passage of the Gulf Opportunity Zone Act of 2005, more of the tax-free benefits from the Katrina disaster have gone to the Louisiana’s powerful oil industry than to development in hard-hit areas. According to Newsweek,

New Orleans has so far received a total of $55 million in bonds shared between eight projects—or less than 1 percent of the more than $5.9 billion issued statewide. None of the bonds issued for New Orleans projects went to development in hard-hit and still-struggling areas like the Lower Ninth Ward.

Instead, the federal largesse has been poured into oil companies operating far from New Orleans. Since Congress’s unanimous approval of the GO Zone Act, Louisiana officials have issued nearly $1.7 billion in tax-free bonds—about one third of the total issued—for projects that contribute to the production of oil.

I blame the Democrats for continuing with the bankrupt policies and strategies of the past and their continued reliance on organizations and institutions that haven’t conjured a new idea since the 1970s. I blame the Republicans for equating environmentalism with socialism (although I admit that both have relied on strong central government and coercion rather than consent), and for their mindless opposition to our issues no matter the stakes. I especially blame rational members of both parties for not stepping outside of party ideology and allowing themselves to intelligently consider the conservation challenges of our time. As Huey Long said,

The only difference I ever found between the Democratic leadership and the Republican leadership is that one of them is skinning you from the ankle up and the other, from the neck down.

Finally, I blame many in the conservation movement for divesting themselves of an honorably passionate past in the quest for political aggrandizement and financial reward. The Gulf gusher can still serve as a catalyst for change within the conservation and environmental communities. Good can be salvaged even from the wreckage of the Gulf. As I said earlier, there is nothing that I find agreeable in the Tea Party, with one significant exception. At least the Tea Partiers know when to be angry. They are often furious at the wrong people about the wrong issues, but at least they show up. Anger is a potent catalyst, and the time has passed for us to kindle that fire.

[Let me add a comment about the Tea Party. The degree to which the Tea Party is viewed favorably is a measure of how disenfranchised people feel at this moment. The fact that much of the economic and social malaise can be dated to the Bush administration is irrelevant. We elected Obama as a force for change, not to enforce a status quo. The Democrats will be spanked in November, and we will see if this president learns his lessons and salvages his legacy in the last two years of his first term. At this moment, he has only himself and his fellow Democrats to blame.]

We should begin by stripping ourselves of rote partisanship and start embracing an advocacy that towers above politics. Political leaders are not preordained to failure or success. Change is always possible. The advocate’s responsibility is to point out failures, no matter one’s political affiliation, and to suggest measures that may succeed. Spare us the platitudes. With measurable, tangible results will come our support, and not before.

The Gulf would be a perfect place to begin.

Ted Eubanks

26 September 2010