It was passed from one bird to another,

the whole gift of the day.

The day went from flute to flute,

went dressed in vegetation,

in flights which opened a tunnel

through the wind would pass

to where birds were breaking open

the dense blue air –

and there, night came in.

When I returned from so many journeys,

I stayed suspended and green

between sun and geography –

I saw how wings worked,

how perfumes are transmitted

by feathery telegraph,

and from above I saw the path,

the springs and the roof tiles,

the fishermen at their trades,

the trousers of the foam;

I saw it all from my green sky.

I had no more alphabet

than the swallows in their courses,

the tiny, shining water

of the small bird on fire

which dances out of the pollen.

Pablo Neruda

The American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) has reshuffled the birding world, and bird people are checking their lists to find the winners and losers, the splits and the lumps. The splitters have dominated for the past several years, and I see no overcoming their hegemony. Why complain? I gain a whip-poor-will and a wren without lifting the binocs.

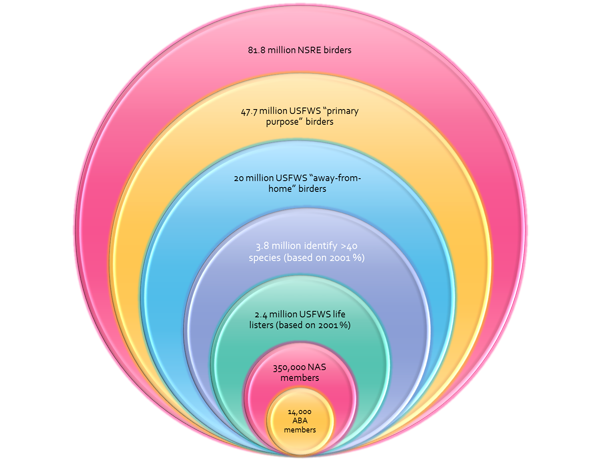

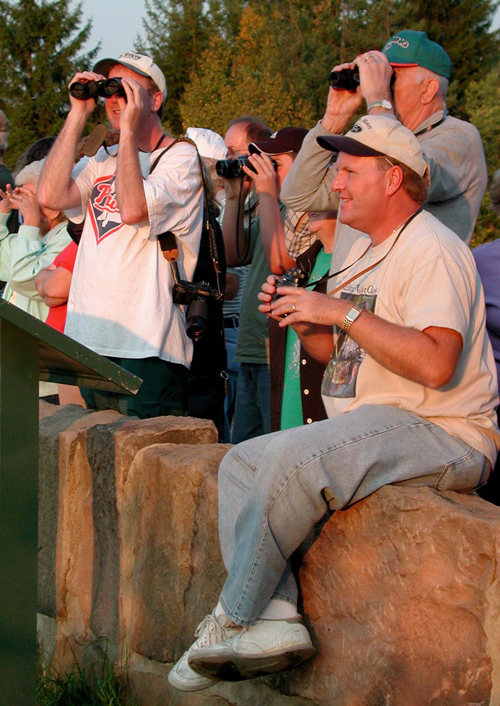

Birders obsess over the typology of birds. I obsess over the typology of birders. For years I have tried to understand the diverse ways people approach nature through birds. I know; the word “birdwatcher” conjures visions of mossy pith helmets, khaki shorts framing pallid legs, and Miss Jane Hathaway. But there are over 80 million bird people, and surely not all are as geeky as the spoofs would imply. For God’s sake, Ian Fleming named his fictional spy (Bond, James Bond) after one of the bird people!

Who are these bird people? Let’s return to the National Survey of Recreation and the Environment (NSRE), the survey that cuts the broadest swath across the birding world. The NSRE asks the following questions in their telephone surveys of Americans 16 and older:

During the past 12 months, did you view, identify, or photograph birds outdoors?

Respondents that answered yes are then asked the following question:

On how many different days did you view, identify, or photograph birds outdoors?

A sample that the NSRE believes accurately reflects 81 million Americans answered yes to the first question. What astounds me is that anyone would answer no. What sentient human on this planet has not viewed a bird in the past 12 months, the visually impaired notwithstanding? How many people in this country have not seen or heard a bird today? I know, there are shut-ins for whom nature is shut out. But for the rest of us, just open the front door or the shades.

Let’s begin with the assumption that the NSRE respondents believed “view” to mean a concerted effort rather than incidental contact. If so, there are over 80 million Americans who have consciously approached nature through birds – the bird people. Within this amorphous mass there is a small segment we label as birdwatchers or birders. The vast majority are titleless. Most enjoy birds around the home, and may get no more advanced in skill than recognizing a chee-chee bird at the feeder.

Is this world of bird people so unfaceted, so simple as to be inhabited by a homogeneous people who only “view, identify, and photograph?” Enter typology. We know thousands of species of birds. What about the species of birders?

To develop a typology of bird people we must first strip away the obvious and look closely at how motivations are manifest in behavior. In other words, what are all of the ways that an interest in birds is reflected in how bird people act? What brings people to birds in the first place, and what keeps them engaged? Why do a few identify with the name “birder,” while most don’t?

I will start with the watchers. There are bird people who watch all birds, and collect their experiences in the form of a list. In the U.S., to list 700 species is considered a milestone accomplishment. There are watchers that have life lists, state lists, county lists, city lists, yard lists, and even feeder lists. Some bird people count the birds seen each year, and others try to see the most in a single day. Some count hawks, some shorebirds. Many watch at night, others from the deck of a boat (pelagics, whooping cranes, puffins). I have known people who kept a list of birds seen or heard while watching television and movies (surely you remember the kookaburras and peacocks echoing through Tarzan’s jungle).

There are times when bird people count collectively. There are Christmas bird counts (CBC), breeding bird surveys, hawk watches, eagle watches, feeder watches, great backyard bird counts, big days, big sits, and international migratory bird days. Lists are kept on paper, in journals, in software programs, and virtually (eBird). Bird people identify the birds they count by field marks, field notes, songs, flight calls, and “giss” (general impression, shape, and size). Bird people gather at bird festivals, bird fairs, and bird events. There are vulture festivals, eagle festivals, shorebird festivals, swallow festivals, and hummingbird festivals.

Bird people join organizations and clubs, such as the National Audubon Society, the American Birding Association, state ornithological societies, and local bird clubs. Many join just to receive a magazine or newsletter. Each activity, event, organization, and periodical attracts an infinitesimally small fraction of the bird people. The bird people are the elephant in the bathtub, yet most serving them see only a leg, foot, or trunk.

There are bird people that watch but do not keep lists (I am one of the listless). Some try to place a name on every bird seen, while many are content to experience nature through birds without a need for further analysis or understanding. There are those who will spend thousands of dollars on equipment, and some are happy with a $25 pair of Tascos. I know accomplished bird people who carry nothing more than a dog-eared field guide and a pair of Army surplus binoculars, and incompetent birders who are well-adorned gear-heads. There are traditional bird people who rely on optics, and others who watch birds migrate with Doppler radar and track them by satellite. Many watch birds on their computers (feedercams, nestcams). Bird people watch owls and goat-suckers at night (and migrants crossing the full moon), and others record bird sounds with ARUs (Autonomous Recording Unit).

There are watchers who memorialize what they see in ways other than ticking a name off of a list. For example, there are bird people who photograph birds, digiscope birds, draw birds, paint birds, record bird songs, video birds, and keep notes and journals about bird sightings. Bird people then submit their notes and recordings of rarities to other bird people who serve on bird committees. Bird people maintain rare bird alerts, phone messages, and email lists such as Birdchat. There are a select few who devise new ways of identifying birds (ID Frontiers). There are bird people producing bird programs on radio, television, and video. There are even bird people movies such as Winged Migration, March of the Penguins, and the forthcoming Big Year.

There are bird people who express their watching experiences through art. Pablo Neruda wrote poems about watching birds. Salvidor Dali included a barn swallow in Still Life – Fast Moving, and crows were among Van Gogh’s final subjects in Wheat Field with Crows. Tom Robbins’ Still Life with Woodpecker is perhaps his best writing, and of course Peter Matthiessen has written about birds and nature often during his splendid career. I find it heartening to know that Neruda, Dali, Van Gogh, Robbins, and Matthiessen are bird people too.

But bird people memorialized birds in art millennia before the impressionists. I have seen peacocks painted on the walls of Tao shrines in China, ocellated turkeys in Mayan glyphs, and a kingfisher exquisitely illustrated in a Hiroshige woodblock print. The Egyptians including cranes and falcons in their monuments, Native Americans carved owl faces in their rock art, and Australian aboriginals painted the extinct Genyornis on cave walls over 40,000 years ago.

Writers and artists describe and illustrate birds also as a way of educating and informing. Bird people write and illustrate identification guides (such as those by David Sibley, Kenn Kaufman, and National Geographic), organize bird trails, and create weblogs about birds and birding (such as Birdspert, and 10000 Birds). Yet within each of these subsets there are further divisions. We have yet to reach the atomic level of watching. For example, there are people who photograph from a blind, others who shoot from the window of their car, and some use high-speed flash. There are those who like to photograph birds on the wing, those who prefer the closest cropped view, and others, such as the Japanese, who photograph birds within a broader landscape.

There are bird painters who use water colors, and others who paint in oils. There are sketchers, illustrators, and print-makers and lithographers. There are painters who strive for realism, others for impression. People carve birds, mold birds, and cast birds. A few people paint only hummingbirds, others only ducks. In my Galveston home there are prints by Audubon, Gould, Fuertes, Peterson, John O’Neil, GM Sutton, Don Eckelberry, and Lars Jonnson. I am surrounded by bird people.

What about the bird-feeding bird people? Aren’t they watchers too (I doubt that many are feeding birds to fatten them up.)? There are gardeners for whom birds are a byproduct of the urban landscape. Many people are content to hang a couple of seed feeders from an eave, others manage intricate bird cafeterias with nectar, water, suet cakes, fruit, meal worms, wax worms, and various seeds and nuts on the menu. In the north people feed hummingbirds in the summer, and along the Gulf coast in the winter. Rather than install feeders, there are bird people who would rather cultivate native habitat around the yard, ranch, or farm to attract birds. Some install bird baths, others elaborate ponds. Some build bird houses, some buy and install the same (for bluebirds, for example), some people and even communities erect elaborate hotels for purple martins, and others construct artificial chimneys for swifts. Many of these feeder/garden/bird house people are organized. There is the Purple Martin Conservation Association, the Hummingbird Society, and ChimneySwifts.org. Some participate in Cornell’s Feeder Watch. Others subscribe to specialty magazines (Birds and Blooms and Bird Watchers’ Digest, for example).

Of course there are other bird people who supply the bird feeder people. There are bird people that manufacture (Droll Yankee feeders, Perky Pet), retailers (Duncraft, Wild Birds Unlimited), and websites (The Backyard Bird Company, JustBirdHouses, and BirdWatcher Supply Company). At backyardbird.com, you can order a bird house with your favorite NFL team’s insignia emblazoned on the front. Big Pockets provides clothing for birders, and Nikon, Swarovski, and Bushnell are among the optic manufacturers. Google the words “birdwatching supply” and see the reach of the market. Non-profit nature centers sell birding stuff, CLO sells birding stuff, Walmart sells birding stuff, National Geographic sells birding stuff, and ABA sells birding stuff.

There are bird people who offer services to other bird people. There are bird lodges (Pico Bonito in Honduras, Asa Wright in Trinidad, and O’Reilly’s in Australia are among my favorites), and bird guide companies that will take you to them (Victor Emanuel Nature Tours, Wings, and Field Guides, for example). There are bird tourism agencies and staff, marketing bird experiences such as the Wetlands and Wildlife Scenic Byway in Kansas or the World Birding Centers in South Texas. There are companies, such as Fermata, that help bird companies connect with other bird people.

Bird companies are bird people too.

Then there are the people who hunt birds. Of course all intentionally view birds as well, even if only down the barrel of a shotgun. There are bird hunters who stalk upland birds such as pheasant and quail, and others who find pleasure in freezing in a duck blind. There are bird people who hunt cranes, rails, snipe, and woodcock. Some hunters are after dove in the fall, others turkey in the spring. Some use dogs, others master bird calls. Bird hunters have not only separate interests but separate organizations as well, such as Pheasants Forever, Ducks Unlimited, Quail Unlimited, the Ruffed Grouse Society, and the National Wild Turkey Federation. If a hunter responds affirmatively to the NSRE survey, he (hunters are predominantly male) becomes one of the bird people as well.

These types of hunting are legal and controlled. Other types are not. There are kids killing yard birds with pellet guns. In many countries (such as Mexico), there are bird people who make their living by trapping and selling caged birds. Many of the trappers know precisely the names and habits of the birds they capture. Are these bird people too? Aren’t they intentionally viewing?

Bird people express, watch, feed, and hunt. They also study and teach. There are scientists for whom birds are the primary subject (ornithologists), and others for whom birds are indicators (ecologists, for example). There are universities such as LSU and Cornell with renowned schools of ornithology. There are bird educators, both formal and informal. Bird people lead field trips, conduct seminars, and speak at gatherings of other bird people. There are bird education organizations such as the Bird Education Network, Flying WILD, and Cornell’s Project Urban Bird. Bird people band birds during migration, at night (like owls at Whitefish Point), some for research, and others to ring and fling. A few collect birds as specimens, others collect birds as points of data.

There are bird scientists who study bird conservation, and others who manage conservation in the field. There are game and nongame bird biologists. There are professional bird students, and nonprofessional bird teachers. I know bird people who inventory proposed sites for wind power development, and others who study endangered species threatened by oil spills. In recent years many bird people have become involved with identifying important bird areas (IBAs), and compiling breeding bird atlases. There are bird laboratories and bird observatories, with some specializing in research (Point Reyes and Powermill), some in education (Black Swamp, Cape May), and others in conservation (Gulf Coast Bird Observatory).

There are people who rehabilitate injured birds, those who clean oiled birds, and some who become vets in order to better care for birds. There are a number of formal bird associations and societies, such as the American Ornithologists’ Union, the Association of Field Ornithologists, the Cooper Ornithological Society, the Neotropical Ornithological Society, the Pacific Seabird Group, the Raptor Research Foundation, the Society of Canadian Ornithologists, the Society for the Conservation and Study of Caribbean Birds, The Waterbird Society, and the Wilson Ornithological Society. These are serious bird people.

Bird people are also in the public’s eye. Two former presidents were (and are) bird people – Theodore Roosevelt and Jimmy Carter. As a young man Roosevelt even toyed with becoming a biologist, and he kept a detailed list of all the birds he saw on the White House grounds during his presidency. The brief movie below is from the 1915 trip to Breton Island (LA) by Roosevelt, the only one of his refuges he personally visited. Former Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger and former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson are bird people as well. In 1948 Whittaker Chambers tripped alleged spy Alger Hiss with a prothonotary warbler. Count Jane Alexander, George Plimpton, Agatha Christie, and Ian Fleming among the bird people too.

There are people who rehabilitate injured birds, those who clean oiled birds, and some who become vets in order to better care for birds. There are a number of formal bird associations and societies, such as the American Ornithologists’ Union, the Association of Field Ornithologists, the Cooper Ornithological Society, the Neotropical Ornithological Society, the Pacific Seabird Group, the Raptor Research Foundation, the Society of Canadian Ornithologists, the Society for the Conservation and Study of Caribbean Birds, The Waterbird Society, and the Wilson Ornithological Society. Yes, these are bird people as well.

Bird people are also in the public’s eye. Two former presidents were (and are) bird people: Theodore Roosevelt, and Jimmy Carter. As a young man Roosevelt even toyed with becoming a biologist, and he kept a detailed list of all the birds he saw on the White House grounds during his presidency. Former Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger and former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson are bird people as well. In 1948 Whittaker Chambers tripped alleged spy Alger Hiss with a prothonotary warbler. Count Jane Alexander, George Plimpton, Agatha Christie, and Ian Fleming among the bird people too.

I have even known bird people named for birds (names either by their parents or later changed; I’m not asking.). I know a cerulean (Susan, one of the creators of the Great Florida Birding Trails), a shearwater (Deborah, whose company guides people to see pelagic species such as shearwaters), and a mallard (Larry, who managed wildlife refuges in Arkansas when I knew him). The former president of the National Audubon Society is John Flicker, and the current chairman of the board is Holt Thrasher.

And then there are the conservation bird people. Some come to conservation through birds, others to birds through conservation. There are volunteer bird conservationists, professional bird conservationists, and bird conservation organizations such as the American Bird Conservancy and the National Audubon Society. There are those groups that conserve habitat that benefits birds (The Conservation Fund, The Nature Conservancy, Trust for Public Land, American Land Conservancy, local land conservancies). There are conservation organizations that specialize in certain birds (International Crane Foundation, the Peregrine Fund, the Western Hemispheric Shorebird Reserve Network), and others that focus widely (Birdlife International, The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds). Some organizations, like Partners in Flight, bring conservationists, scientists, and educators together in coalitions.

Bird conservation groups work at the state level (Mass Audubon, New Jersey Audubon), and some locally (such as the Houston Audubon Society and Hawk Mountain). Federal and state agencies promote bird conservation, manage bird refuges and sanctuaries, and enforce bird conservation laws and treaties. Cities such as Houston, Chicago, and Philadelphia have signed the Urban Conservation Treaty for Migratory Birds. I have known staff from bird organizations that eagerly raised funds for birds they knew nothing about. I have known crusaders that would slip in the name of an endangered bird at the drop of a hat if it bolstered their argument. And I have known many, many bird people who blithely ignored the bush with the bird.

Who are the bird people? All of this, and more.

Birdwatching is a Victorian pastime that overnight morphed into a 21st Century recreation – birding. Birding has the flexibility to allow each person to fit the interest to themselves. The constraints that once limited birding (where to go, what to see) have been shattered by technology. Along with the transformation of watching, other aspects have been fundamentally altered. When I began birding scientists were still arguing whether or not birds migrated across the Gulf of Mexico. Now we can watch them on Doppler from the comforts of our living room. As as kid we bought striped sunflower seed (the only type available) at the feed store. Now I go to Wildbirds Unlimited and have access to every type of seed, feeder, and accoutrement I can imagine. Birds and their watching have become a big business, fueled by the growing appetite of the bird people.

Birds bind people together. No human being aware of their surroundings has lived absent birds. Birds offer a lingua franca for describing nature, and a portal for approaching the world outdoors. No matter how divergent our evolution, we all converge upon a notion expressed so sublimely by bird person (and Nobel Laureate) Pablo Neruda:

A people’s poet,

provincial and birder,

I’ve wandered the world in search of life,

bird by bird I’ve come to know the earth.